I photograph infrastructure because it’s the physical manifestation of our societal beliefs around who and what we consider to be valuable, and what we choose to protect.

1

- 1Hanusik, Victoria. Twitter Post. August 5, 2021, 5:44 PM. https://twitter.com/virginiahanusik/status/1423399436080852999

Notes on the Field Notes

This is a time of crisis. We, the founding iGND contributors

2

,

We focus our attention on the Climate Crisis for three reasons. One is that the built environment—the realm landscape architecture, architecture, city planning, and the other spatial disciplines ostensibly shape—is a critical site of contestation in the fight for climate justice. From our perspective, discourse around the Green New Deal has been far too focused on abstract macroeconomic principles, technological innovation, and a broad bias toward ecomodernism.

3

- 2Link to Contributions page

- 3Monbiot, George. “Meet the Ecomodernists: Ignorant of History and Paradoxically Old-Fashioned.” The Guardian, September 24, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/georgemonbiot/2015/sep/24/meet-…

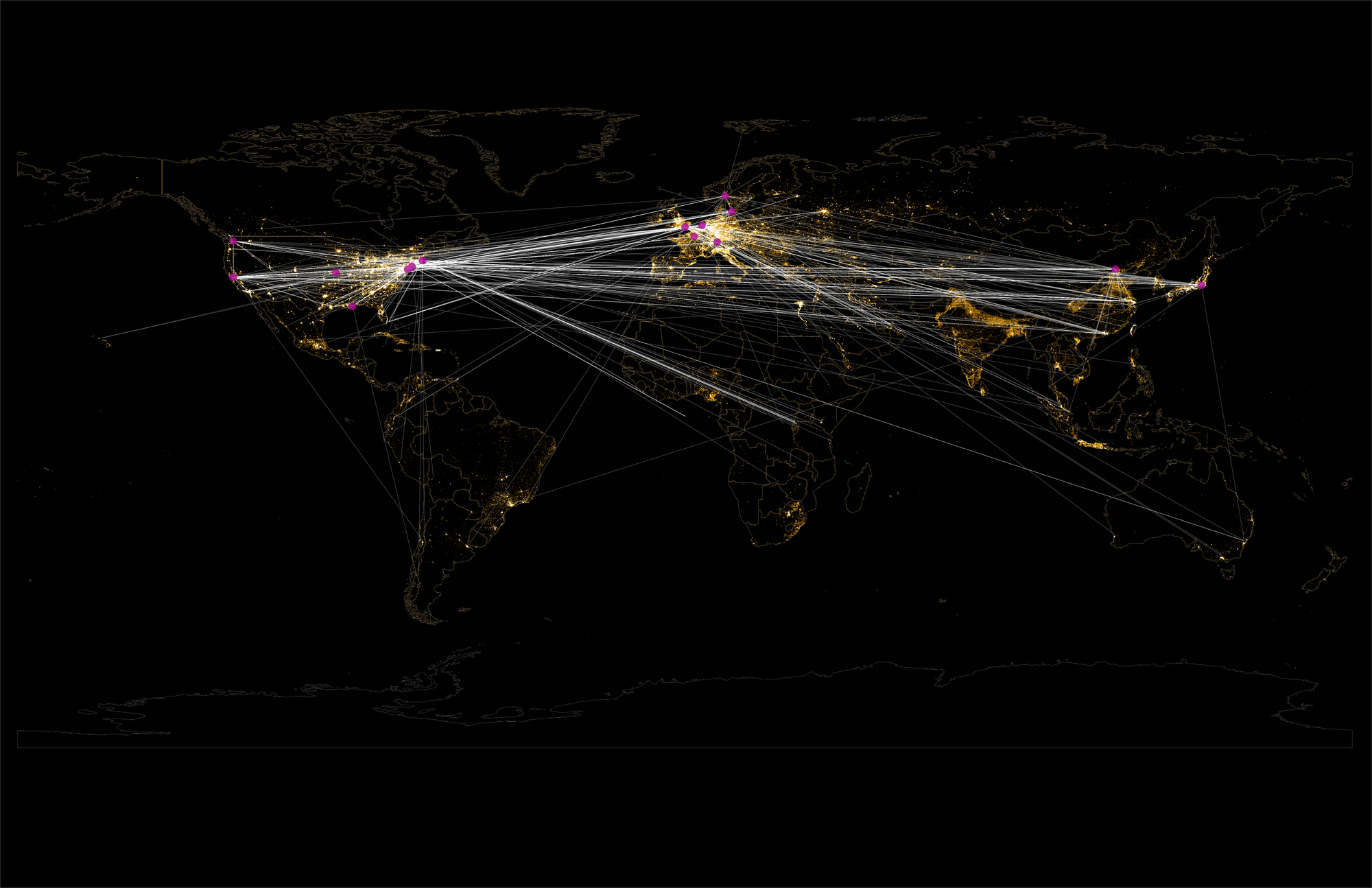

Map of the globe showing the sub-national GDP (light orange), headquarters for the largest multi-national design firms in operation (purple), and their publicly listed projects from this century (white). Visit Global Design Praxis to learn more.

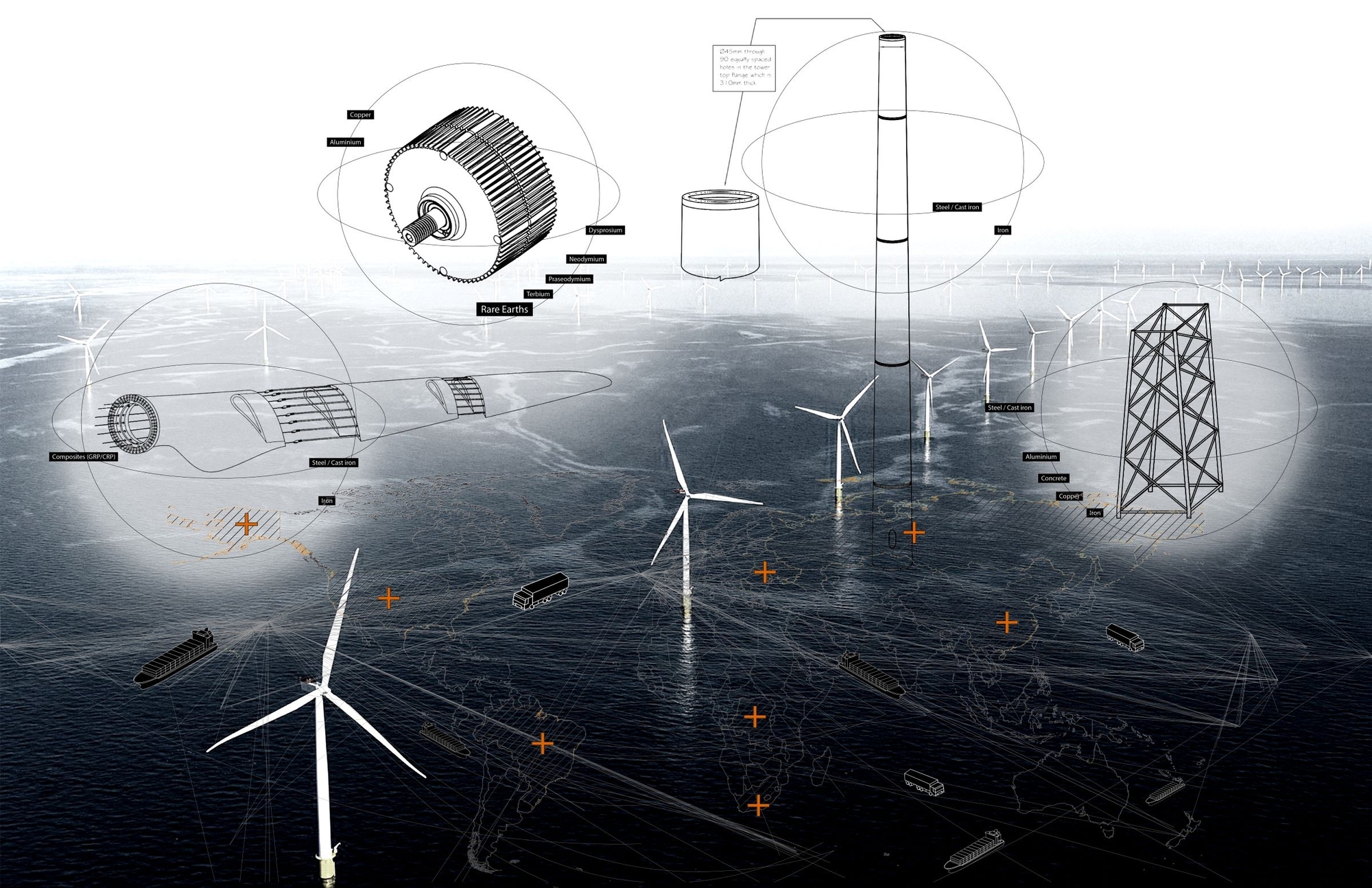

A second reason for initiating this project is that calls for a Green New Deal in the US are often divorced from a core question: what will the consequences of an American energy transition be for the rest of the world? The rare earth minerals and other raw materials; the labor to extract, process, and ship new technologies; all of these have the potential, and very likely possibility, to reproduce extractive and exploitative regimes and supply matrices

4

Finally, Field Notes takes the Climate Crisis as its object of study because any response to it—Green New Deal or otherwise—will necessarily include a massive transformation of how and where most people live. Yet little, if any, attention thus far has been paid to questions of how to balance that need for massive construction and deconstruction efforts with desires to practice democracy. Put another way: how will Green New Dealers balance the need to transform the built environment as much as humanity has ever endeavored, as fast and as well as it has ever built anything, with their desire to protect community self-determination and advance desires for justice? Field Notes does not offer easy answers to these vexing questions. But do we hope that it re-frames conversations around climate justice, energy transitions, and the Green New Deal in ways that foreground the spatial and material consequences of them in frontline communities all over the planet.

- 4Link to Supply Matrix Intro

Cladding and roofing details, stone quarries, street and highway illumination schemes, the ambiguous architecture of housing, the form of settlements, the construction of fortifications and means of enclosure, the spatial mechanisms of circulation control and flow management, mapping techniques and methods of observation, legal tactics for land annexation, the physical organization of crisis and disaster zones, highly developed weapons technologies and complex theories of military manoeuvres—all are invariably described as indexices for political rationalities.

- 5Weizman, Eyal. Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso, 2017.

In order to set that frame, this introductory essay focuses on the infrastructures at the root of the climate crisis—the roadways, railways, buildings, and broader built environment of high carbon injustice, something we refer to as the “infrastructural evidence” of political economic regimes. To do this, we rely in part on Berlant, who describes infrastructures as “all the systems that link ongoing proximity to being in a world-sustaining relation”

6

The remainder of this essay is structured around conceptualizing infrastructure and/as ideology, relating this framework to the kinds of worlds that a Green New Deal might make possible, and outlining the rest of the material contained within Field Notes. As readers will surely note, the content in this project is expansive, ranging from critical cartographic images of the state of global design practice and megaprojects to more speculative visions of the supply matrices underpinning the production of lithium batteries

7

- 6Berlant, Lauren. “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times*.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 3 (2016): 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989.

- 7Link to Lithium Battery piece

- 8Link to Wind Turbines piece

Map of the globe showing the supply chain for production of lithium-ion batteries. Visit Supply Matrix to learn more.

Infrastructures and Ideologies

Though the built environment and its designed transformations are often romanticized as drivers of social, political, cultural, and economic change, Field Notes operates from the position that it is, instead, a simple manifestation of (often) elite social, political, cultural, and economic preferences. Rarely, if ever, is it reflective of a broader polity or social movement. Rarer still is it a driver of—rather than manifestation of—the kinds of structural forces already transforming how and where most people live.

Field Notes takes the planetary and multi-scalar sets of relations described above as a framework for probing and positing what it might mean to realize an internationalist Green New Deal. If “all systems that link ongoing proximity to being in a world-sustaining relation” is our conceptual framework for understanding infrastructure as it actually exists, then the alternative physical, social, and ecological arrangements that other, future worlds may create becomes our framework for a set of utopian imaginaries, rooted in abolition and decolonization, and instrumentalized through the projects a Green New Deal might make possible.

At the core of this worlding exercise is a question posed by Anand, Gupta, and Appel: “[if] infrastructure is a terrain of power and contestation, [then] to whom will resources be distributed and from whom will they be withdrawn?”

- 9The social production of space has widely been acknowledged and expanded upon following Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space. Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2009. For more recent discussions on the impacts of infrastructure distribution, social production, and environmental justice see “The Infrastructures of Equity and Environmental Justice'' by Marccus Hendricks. Hendricks, Marccus D (2017). The Infrastructures of Equity and Environmental Justice. Doctoral dissertation, Texas A & M University. Available electronically from https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/161342. For the importance of urban social infrastructures in community resilience see Palaces for the People by Eric Klinenberg. Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. New York, NY: Broadway Books, 2019.

- 10Weizman, Eyal. Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso,2017.

- 11Brenner, Neil, ed. Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization. Berlin: Jovis, 2013.

- 12Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, eds. “Introduction: Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure.” Essay. In The Promise of Infrastructure a School for Advanced Research Advanced Seminar, 1–40. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

- 13Purifoy, Danielle and Louise Thompson. “Creative Extraction: Black Towns in White Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39, no. 1 (2020): 47-66.

- 14Link to Carceral Infrastructure

- 15Robinson, Cedric. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1983.

Climate justice and reparations are the same project: climate crisis arises from the same political history as racial injustice and presents a challenge of the same scale and scope. The transformations we succeed or fail to make in the face of the climate crisis will be decisive for the project of racial justice, and vice versa.

To consider how this moves from the abstract to the built environment, we also look to Rivera’s analysis of disaster colonialism in Puerto Rico, writing that “the logics of colonialism, modernity, and capitalism all have their genesis in the Caribbean...the convergence of socio-environmental and political struggle gains traction if we recognize that colonialism, in its fundamental manifestation, implies the exploitation and extraction of minerals and other natural resources, as well as the plundering of material, cultural, and environmental goods from the colonized territory.”

In the American context, the through lines between racial and global capitalism, imperialism, and colonialism are often most evident in the production of infrastructure and the built environment. Or, as Hendricks argues, that “environmental prosperity or demise is a direct result of social vulnerability in terms of neighborhood, race, ethnicity, and class and the built environment is exactly the physical manifestation of social circumstances.”

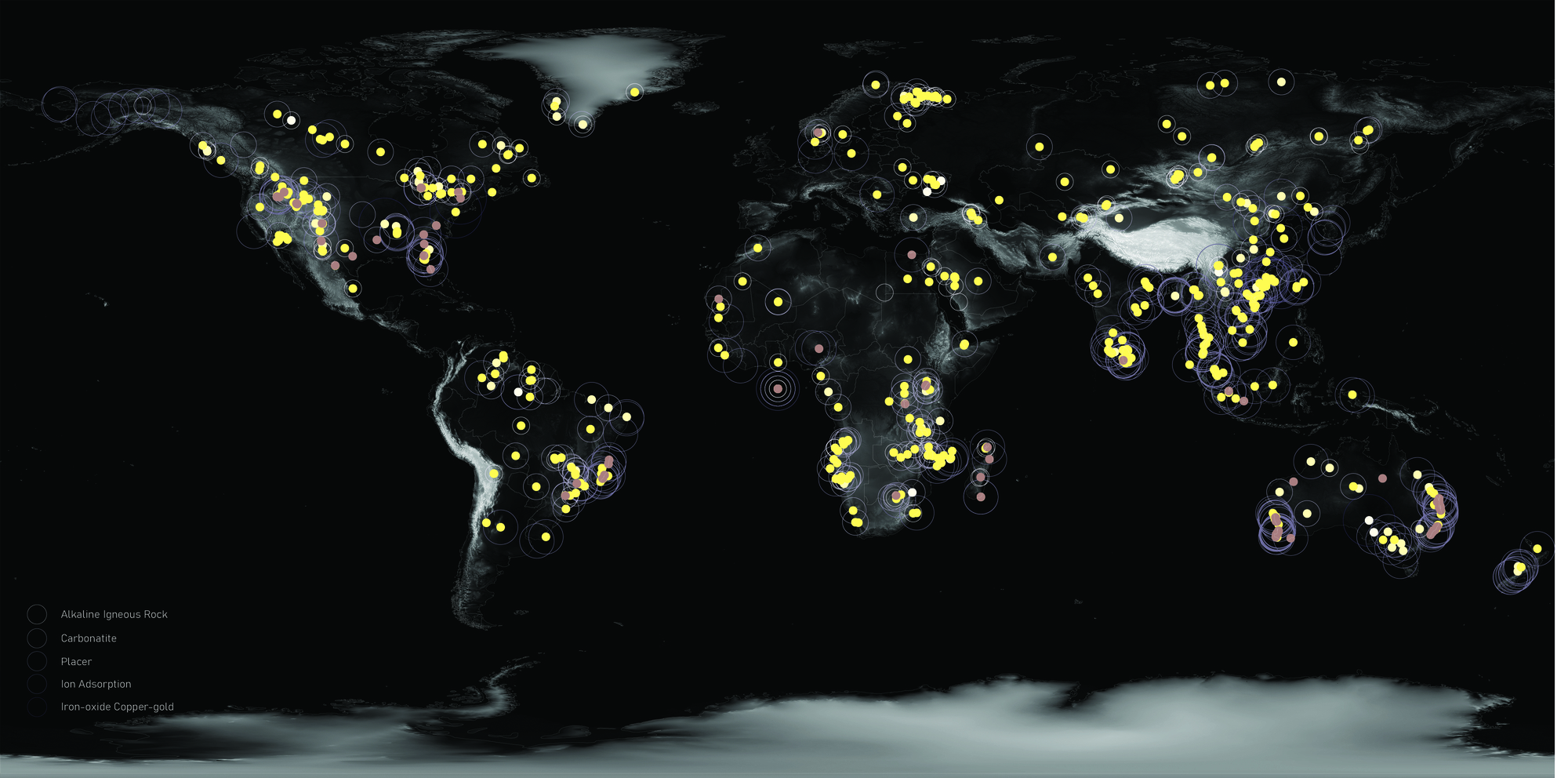

These kinds of relations—poor, working class, and communities of color are treated as sites of accumulating ecological externalities—are reproduced throughout the world by the same systems of oppression and extraction. Rare earth mineral frontiers in Chile, China, the Congo, Greenland, and Nevada

18

- 16Rivera, Danielle Zoe. “Disaster Colonialism: A Commentary on Disasters beyond Singular Events to Structural Violence.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 46, no. 1 (2020): 126–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12950.

- 17Hendricks, Marccus D (2017). The Infrastructures of Equity and Environmental Justice. Doctoral dissertation, Texas A & M University. Available electronically from https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/161342.

- 18Klinger, Julie. Rare Earth Frontiers: From Terrestrial Subsoils to Lunar Landscapes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

- 19Arboleda, Martin. Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction Under Late Capitalism. New York: Verso, 2020.

Map of the globe showing rare earth deposits around the world in relation to the quantity of minerals yet to be extracted. Visit Rare Earth Elements to learn more.

Situating Field Notes Toward an Internationalist Green New Deal

Built environment professionals may find it disappointing to learn that simply adding “green” to a concept or project title—or stamping “Green New Deal” atop their work—does not mean much of anything. Across the globe, so-called “green” climate solutions and infrastructures tell us less about the content of a project or initiative and far more about the ways in which global racial capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism can creatively reinvent, repackage, and rescue

22

- 22Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 1, no. 1 (2012).

The initial vision of a radically redistributive program [the Green New Deal], hewn to a divest-invest framework that could deliver transformative improvements in most people’s quality of life and crush the fossil-fuel industry is increasingly at odds with more technocratic, ecomodernist plans centered around clean energy infrastructure (primarily nuclear), carbon capture technology and so-called clean energy standards (including natural gas) delivered by public-private partnerships and market-driven solutions.

23

- 23Fleming, Billy. “Crises and Contestations: The Promise and Peril of Designing a Green New Deal.” Architectural Design 92, 1: 20-27.

The world within and beyond the design industry is already replete with examples of green capitalism. Though they vary in form, aesthetic, framing, and geography, the mechanisms of green capitalism are often united by a shared commitment to protecting and reproducing the (unjust) status quo. Many of them also share an affinity for the synthesis of big data and green energy, delivered through massive physical infrastructure projects that give form and aesthetic to the tenets of ecomodernism. In Greenland, the American Mountain West, Eastern Europe, and much of the world, large-scale energy infrastructure projects are being conceived and built alongside—and often integrated within—industrial-scale data center projects. Their co-location is not a coincidence, it is a feature of this kind of approach to decarbonization. These kinds of projects—the provisioning of new clean energy alongside massive facilities that consume world-historical volumes of energy—are complicating the idea of data centers as one-way consumers of energy and the idea of renewable energy as a substitute for oil and gas. In many cases, renewables are being deployed to simply add more power to the grid—power that’s needed to keep the burgeoning cryptocurrency industry afloat.

This trend is especially visible in the blockchain space, where the future of green energy is not only being coupled with that of cryptocurrency, but also entwined in various ways with other state-led visions of the future. In addition to making Bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele has begun touting the building of a vast geothermal plant to support a government-controlled Bitcoin mining operation.

- 24Alemán, Marcos, and Christopher Sherman. “El Salvador Explores Bitcoin Mining Powered by Volcanoes.” AP NEWS. Associated Press, October 15, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/cryptocurrency-technology-business-bitcoin-c….

- 25Asay, Matt. “Bitcoin ‘Incentivizes Renewable Energy’ Says Twitter's Dorsey. Is He Right?” TechRepublic, January 18, 2021. https://www.techrepublic.com/article/bitcoin-incentivizes-renewable-ene….

- 26“U.S. Energy Information Administration -EIA -Independent Statistics and Analysis.” International -U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2019. https://www.eia.gov/international/overview/country/SLV.

Climate infrastructure and systems of climate justice need to operate at the speed and scale of the internet’s deployment to effectively address the Climate Crisis in the first half of the 21st century. Visit The Internet to learn more.

This form of infrastructural green capitalism extends to the African continent too. There, buoyed by the direct and “flexigemonic” power of Chinese state-led investment, a raft of speculative built environment projects are transforming communities, nations, and regions across the continent. One example can be found in the utility-scale wind farm emerging along the blustery Dakhla Peninsula in Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara. Built on the promise of providing abundant energy to an under-served population through utility-scale wind power production, it too is predicated on the co-location of clean energy infrastructure and industrial-scale cryptocurrency mining to operate.

- 27Li, Yan, Eugenia Kalnay, Safa Motesharrei, Jorge Rivas, Fred Kucharski, Daniel Kirk-Davidoff, Eviatar Bach, and Ning Zeng. “Climate Model Shows Large-Scale Wind and Solar Farms in the Sahara Increase Rain and Vegetation.” Science361, no. 6406 (2018): 1019–22. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar5629.

[T]o power the blockchain with clean, renewable energy that we own and control. Soluna will address the growing demand for energy to power today’s growing blockchain networks, and will create the world’s first ‘service node’, providing high-density computing for future blockchain networks. 28

- 28“SolunaBuilds Wind-Powered Blockchain Computing Facility in Morocco.” Power Technology, July 31, 2018. https://www.power-technology.com/news/soluna-building-wind-powered-bloc….

For the first few years of its operation, this wind farm will function entirely off-grid, meaning that one-hundred percent of the power generated by the phalanx of turbines that will dot the Dakhla Peninsula will be funneled into a nearby data center. Its sole function will be to mine cryptocurrency and provide enterprise blockchain solutions to international firms. From the outside, the end-goal of this endeavor seems obscure, and altogether ridiculous considering the anticipated size and capacity of this wind farm (900mw/h, roughly enough to power an average American city of a little over 300,000 like Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, or Honolulu). The deployment of this project becomes all the more puzzling when one realizes that Morocco does not even permit cryptocurrency transactions within its national borders. Investing state capacity in renewable energy sources that serves a primarily international audience (and provides little, if any value beyond speculative currency manipulation) with no tangible benefit to people living in the region is a far cry from how we and others have framed building an internationalist Green New Deal in practice. But projects like Soluna’s are increasingly common and made possible through the kind of greenwashing described above. It, and projects like it, are being wrapped in futurist imaginaries that incorporate both the global drive for renewable energy, as well as the promise of new technologies like blockchain to build new energy infrastructure intended to serve non-resident bitcoin miners instead of those living with and around the generation, transmission, and storage systems. Through green capitalism, the world is being prefigured by the same tech giants, financial firms, and global elite as before. Only now the dystopian, ecomodernist future comes with 20 percent more green stuff.

An internationalist Green New Deal must not be the worst of all worlds; it must actively resist the simple greening of existing capitalist and nationalistic frameworks for growth. These schema have proven to be extensions of colonial violence and imperial logics of extraction and will not be rescued in a world working toward global climate justice. There is no room for the “green” versions of the same old bad stuff.

Map of the globe showing wind turbines, complex assemblages of material components that are set to be extensively distributed across the globe. Visit Supply Matrix to learn more.

Contemporary green energy projects have already begun to reinscribe lines of colonial violence and extraction.

To build the kind of post-carbon future that an internationalist Green New Deal implies requires grappling with a series of critical, unanswered questions: how might Green New Dealers avoid the possibility of global elite capture and/or reformist compromise? How should Green New Dealers manage the inevitable tensions between the need for expedience—to build more things than have ever been built, as fast and as well as anyone has ever built anything—with their desire to practice democracy and uphold community self-determination? How might the built environment professions build new alignments, skills, and practice communities that narrow the gap between their rhetoric and results? There are no easy answers to these questions—but centering these questions in the realization of an internationalist Green New Deal is key to avoiding the endless attempts to co-opt and dilute the program by guardians of the (unjust) status quo.

These questions, and ones that will arise through collaboration and conversation with others, are a way of orienting toward a shifting version of the future without a clearly defined path. The work of unmaking and remaking the world swiftly, collectively, and most importantly, justly will demand critically interrogating how this work can be achieved. Fundamentally, the internationalist Green New Deal is not a critique of the engineered objects of a green future, but of the methods by which they are sourced, shipped, extracted, developed, deployed, maintained, and built. 195 nationalistic Green New Deals will not achieve global climate justice.

- 29Riofrancos, Thea. Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020. Howe, Cymene. Ecologics: Wind and Power in the Anthropocene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019.

- 30“Report: Morocco Uses Green Energy to Embellish Its Occupation.” Western Sahara Resource Watch, October 2021. https://wsrw.org/en/news/report-morocco-uses-green-energy-to-embellish-….

Toward an Internationalist Green new Deal

At its core, Field Notes is a project intended to open new terrains for scholarship, organizing, contestation, and struggle in the fight for a globally just Green New Deal. Field Notes endeavors to make the historical and ongoing effects of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism on people and communities legible where it was obfuscated; it avoids proposing totalizing solutions and instead invites others to bring more situated forms of knowledge and built environment production to bear on the global energy transition; and it is more akin to an ongoing set of dispatches than a single, standalone report of a view from 30,000 feet of the climate crisis and our many possible futures on this planet. To hold this otherwise cacophonous material together, Field Notes is organized around a set of shared principles:

1. This is Not An Atlas:The aim of this project is not a compendium of concretized mappings, or attempts to claim objectivity or knowledge about a set of territories through geospatial data. Rather, it is an ever-evolving collection of critical inquiries into the global nature of the climate crisis and national, international, or sub-national responses to it through the built and natural environment.

2. We Believe that Political Economies are What Drive the Design Professions: This project will foreground the histories and contemporary realities of colonialism, imperialism, racial capitalism as they manifest themselves in the built and natural environment. We are especially interested in the relationship between how and where design is deployed within these existing frameworks, and how alternative, anti-capitalist/imperialist/colonialist frameworks might restructure how and where our fields operate through an internationalist Green New Deal.

3. We Are Not Problem Solvers: Instead of proposing solutions to crises that are well beyond the realm of what design can or should do, 31 Field Notes recognizes that staying with and moving through—or as Lutsky and Burkholder have suggested, focusing our work on how questions are framed and then probed rather than answered—the contested, messy landscapes of the climate crisis is a best path forward.

4. We Aim to be Accountable: Expanding on Ananya Roy’s concepts of accountable praxis within a power center of empire,Field Notes asserts that global policy can help navigate an internationalist Green New Deal but it can also subject peoples and nations with less power (Global South) to empire and privilege the Global North. Empire can be perpetuated through benevolence as well as conflict. More specifically, we are committed to Roy’s argument that “A praxis of global responsibility cannot simply articulate the duty to intervene, a duty that can call into being 21st-century empire or the civilizing mission of 19th-century colonialism or the diagnosis and reform of 20th century development. It must also insist on answering to those who are the objects of our responsibility. Put another way, it is not enough to be responsible. It is also necessary to be accountable. Working in and through the aesthetic modalities of empire, recognizing how empire aestheticizes power, it expands the concept of politics....and to reveal a consciousness of crisis.” Put another way, this project is both aimed at revealing the exploitative, actually existing power dynamics that threaten to undermine future hopes for a just transition and, over time, to decenter the US in telling these stories.

5. We are Not Objective: Field Notes is, ultimately, about a situated view from many somewheres. It is about overlapping, intertwined, and laminated “landscapes of differential value.”32 There are serious limits to the role that global datasets can play in probing the questions we have put forward. The Nation-state is not the target of the Field Notes, which recognizes the climate crisis impacts sub-national and local peoples, and that global phenomena play out in specific, material circumstances on the ground in local, situated places and communities.

6. We are Developing New Disciplinary Alliances: This project includes work from scholars of science and technology studies, public policy, anthropology, media studies, and many other disciplines that are often disconnected from the more instrumental ways in which design operates. Field Notes seeks to participate in a broader set of conversations about a collective, planetary future that can expand the bodies of knowledge within landscape architecture and open up new lines of inquiry with interlocutors in the humanities, political economy, and sociology.

- 31Roy, Ananya. “Praxis in the Time of Empire,” Planning Theory 5, no. 1 (Spring 2006), https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095206061019

- 32Pulido, Laura. “Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial Capitalism.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 27, no. 3 (2016): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013.

A Call for Collaboration

In this collection, the reader will encounter a series of data visualizations in the form of graphs, charts, and maps standing alongside critical essays that what it might mean to realize an internationalist Green New Deal rather than its more ecomodernist formulations. But this collection is partial and incomplete; it is meant to grow. We, the founding contributors to Field Notes Toward an Internationalist Green New Deal, invite interdisciplinary collaborations to the collection in the form of digital “prospects:” photography, poetry, art, and design as well as essays and visualizations as we have curated. The goal of the piece must be to illuminate some aspect of infrastructures of evidence, climate politics, or climate infrastructure in the context of an internationalist Green New Deal, and must align with the six principles as expressed above.

For submissions or inquires: igndnotes@gmail.com