In mimicking the logics that have underwritten the carbon economy for the last three centuries, renewable energy transitions risk repeating old conventions that end in ruin.

In 2018, the world was introduced to a Norwegian energy company named Equinor. Though the name was new, the company was not. Prior to 2018, Equinor operated as Statoil, Norway’s state-owned Oil and Gas major operating in 32 countries around the world. The company’s reemergence from a boardroom-chrysalis seemed to carry more than aesthetic change into its operations. It was also accompanied by an updated mission statement: “We are engaged in the exploration, development, and production of oil and gas, as well as wind and solar power.”

At a glance, Equinor’s announcement might seem worthy of plaudits. Driving investment into wind and solar energy is a good thing and could be read as the beginning of a kind of market correction—a fundamental shift in business practices as the rising costs of fossil fuel extraction and processing become untenable for companies and consumers. But, crucially, Equinor’s statement is not evidence of a major shift in its or any other fossil major’s operations. Rather, it is simply the latest in a long line of investments in advertising and public relations—more of a precursor to a new ad campaign than anything material. Put another way, this is a rebranding exercise for Equinor, made clear on their homepage which loudly proclaims that “the energy transition is the defining opportunity of our time.”

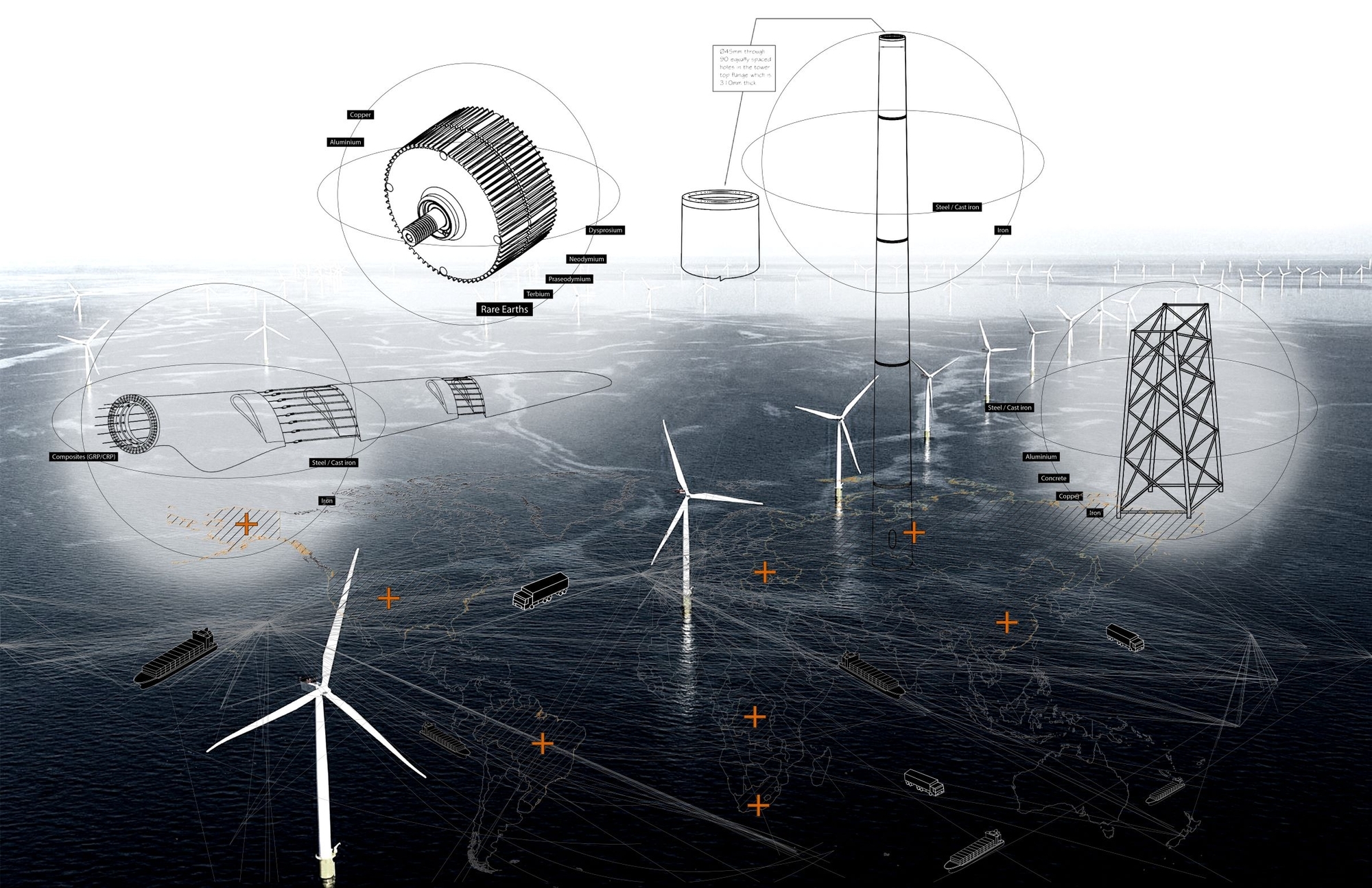

Wind turbines are themselves complex assemblages of material components that are set to be extensively distributed across the globe. Their deployment is undergirded by well-meaning national policies courting clean energy and oil and gas companies attempting to “green” their image. The clean energy transition cannot only benefit those who have caused the Climate Crisis.

Equinor sees the Climate Crisis, one that they helped manufacture, as an opportunity to increase shareholder value through the energy transition. The surreality of such blatant corporate gaslighting aside, for Equinor, and the many other oil and gas companies following a similar path—massive investments in advertising and public relations, a pittance in actual renewable power research, development, and deployment—these interventions are aimed at shifting public opinion. They are not credible plans to decarbonize the economy. The top five oil and gas companies in America, Exxon, BP, Chevron, Shell and ConocoPhillips, spent a combined 3.6 billion dollars over the last 30 years on marketing efforts that promoted their morality, the importance of oil and gas production on advancing society, promoting clean coal and natural gas as a bridge to the future (a line later adopted by President Barack Obama), and spreading disinformation about global warming and their role in exacerbating it.

In most fossil majors, renewable energy investments comprise less than 1% of their annual budgets. Billions, however, have already been spent on marketing, branding, and lobbying campaigns aimed at softening their public image and convincing people and lawmakers that these companies are leading an energy transition—one they are actively fighting in private. Robert Brulle, professor emeritus at Drexel University, has built a body of scholarship revealing the direct relationship between fossil fuel advertising and pending action and hearings in Congress.

In 2017, BP launched its first major ad campaign since the post-Deepwater Horizon oil spill advertising campaign (that campaign approached $100 million). The company touted its new role-out of green energy investments totalling 500 million dollars, including a 200 million dollar investment in solar energy company Lightsource. Left out from these astoundingly large numbers and the advertising campaign, are its parallel investments in oil and gas, totalling 16 billion dollars. That disparity and disingenuous advertising did not go unnoticed, as activists and academics publicly rebuked BP’s claims.

The dynamics of financialisation have made private investors utterly unfit to bankroll a transition, the chase for instant profit taking them even further from a super grid or offshore farm.

Even if their claims of mass investment in renewable energy were true, simply replacing one form of extractivist practice with another does not align with the broader aims of an internationalist Green New Deal. Doing so requires grappling with questions of ownership, the role of the state and industrial policy in driving a just transition, and a global, national, and local restructuring of power dynamics around the principles of energy democracy.

Howe’s concern with deepening ruts of excess and deprivation resulting from the clean energy transition are coming to bear for rural communities across the globe. The low price to rent land from farmers is offset by an extreme profit margin, reaching, on average, at least 2200 times the operating cost after the initial investment is recouped.

The focus on renewed forms of extractivism should not be read as a rebuke of widespread deployment of wind turbines, but as a means to ask a series of critical questions: Who is (and is not) receiving the surplus value of wind? Who is being freshly trapped in existing paradigms of resource extraction? And what geographies are tied together by existing raw material supply chains and the locations of clean energy infrastructure?

While wind energy is a necessary component of a just transition, there is not a technological fix for the Climate Crisis. These gridded landscapes of rhythmically spinning turbine blades are undergirded by complex assemblages of supply matrixes, whirring pillars of material from a diffuse, unevenly distributed territory of rare earth elements and exploited labor. But the story of wind power is less about raw materials than it is about the reproduction of extractivism and global capitalism that it appears to portend. Take for example, RWE (Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk) Energy, a 120 year old energy company headquartered in Germany that operates the largest onshore wind farm in the world, located in West Texas. Like Equinor, RWE recently restructured themselves, allowing them to proudly claim, “From day one, the new RWE will enter the race as one of the international market leaders in the field of renewable energy.”

States and economic-unions have also shown an explicit interest in controlling the flow of core raw materials deemed critical to the implementation of sustainable energy sources and technologies. In the case of wind turbines, rare earth metals are necessary to produce a permanent magnet housed in the nacelle, or outer casing for the turbine engine. Wind turbines typically use NdFeB magnets containing neodymium, praseodymium, terbium, and dysprosium.