For four decades, the U.S. has been engaged in a globally unprecedented experiment to make every part of its criminal justice system more expansive and more punitive.

This essay centers on the US as the most prolific (and dangerous) producer of carceral knowledge and practice in the world. The US, where more people are incarcerated in some individual states than many individual countries, is the laboratory of carceral “innovation,” a grand experiment in human immiseration whose findings are exported across the globe.

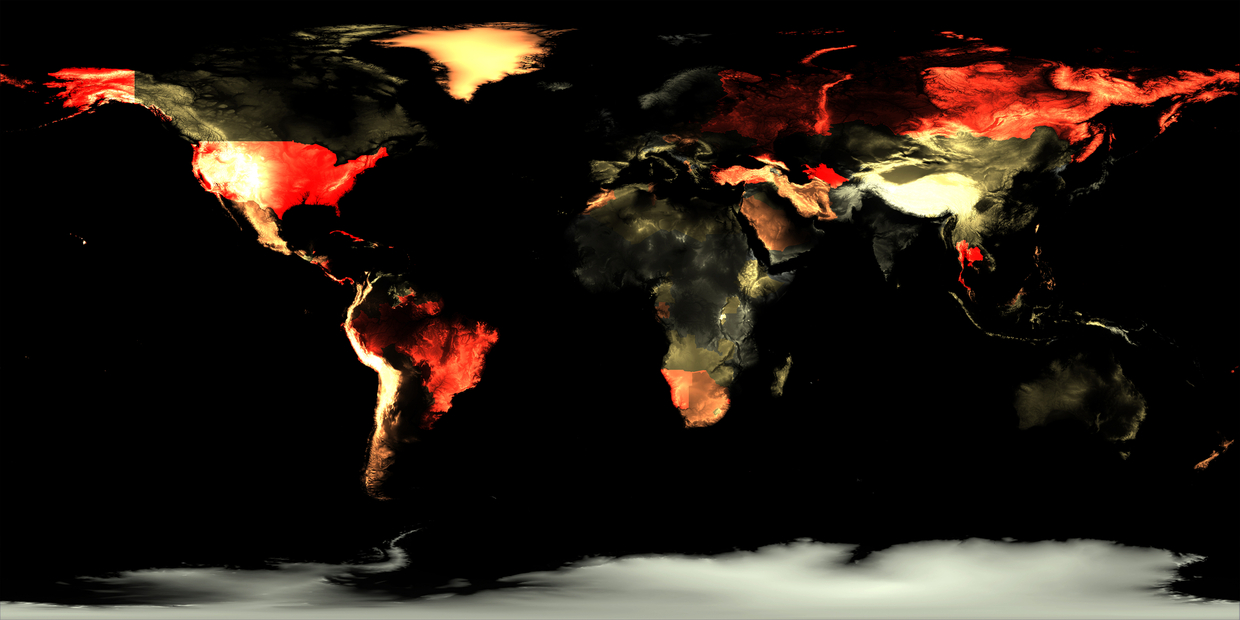

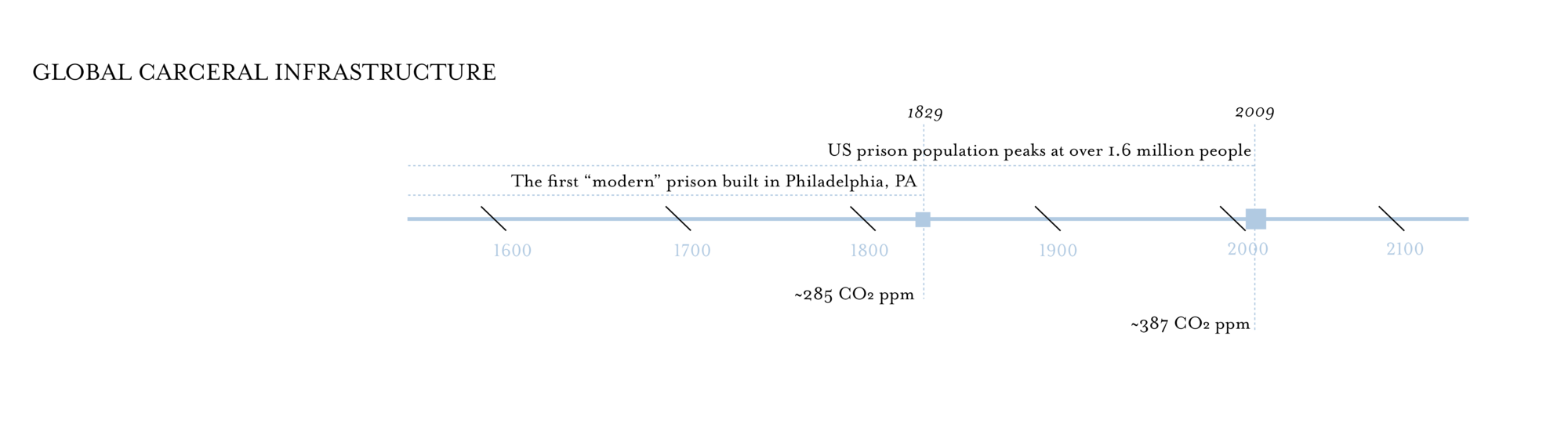

In shades of red, three maps show three complementary relationships to global carceral infrastructure. In the first, the map represents the number of carceral establishments per country, with single-establishment countries highlighted in white circles. The second shows the rate of incarceration per 100,000 people in that country. Carceral geographies are often overlayed with extractive energy landscapes, producing an invisible industry of extraction and entrapment that reifies the logic of racial capitalism. An Internationalist Green New Deal includes global abolition. Everywhere, everyday transformation now!

We turn to Central Appalachia, because nowhere else is it clearer that the story of global mass incarceration is also a climate story–and that they are not two stories that happen to occur in the same place–they are mutually constructive ideologies of global racism capitalism, gender discrimination, and climate colonialism. It is a story of coal and the carceral state.

More than 1.5 million acres of abandoned mine lands pock the undulating landscapes of Appalachia. In its shorn mountaintops and slag-filled valleys, the specter of the region’s long-declining coal industry is literally infused into its place and its people—in the prevalence of human death and disease from toxic exposure to mining and processing coal, in the leachate-filled waterways and aquifers downstream from the mines, and in the dwindling biodiversity that accompanies mountaintop removal. Sometimes described as an internal colony, Appalachia has long been a site of extraction and disposal in the US.

In Eastern Kentucky, the symbolism of new prisons built on top of former coal mines is clear. These facilities infuse local imaginaries with the promise of being the next great form of economic development. Perched atop mountains artificially flattened by industrial dynamite, penitentiaries fill both literal spatial cavities and the economic and affective voids left by coal and the extractive process known as mountaintop removal.

As a result, the region remains one of the poorest in the U.S., with so-called “diseases of despair” like opioid addiction at or near the highest rates in the country.

The prison-building atop abandoned mines complex of Appalachia is driven by major subsidies: namely, the Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Program created by the Surface Mining Control and Remediation Act of 1977. Meanwhile, the land remediation requirements on AML sites are far less stringent for housing incarcerated people on the site than they would be for almost any other residential use.

This Appalachian noir can be understood, at least in part, by viewing the half-century long policy of depopulation through divestment in the region and the 20-year investment in prison-driven economic development as synonymous forces. Central Appalachia is a largely forgotten landscape, underfunded and abandoned by federal policymakers. To borrow once again from Story, that half-century program of depopulation through divestment created a series of spatial, social, and economic voids in the region. These voids then created the conditions for a regional economic development program organized around the carceral system to emerge—one that promised to literally and metaphorically fill those voids with prisons facilities and jobs. Today, the region is now home to one of the largest carceral archipelagos in the world. As Story writes,

To view them in this way is to see an invisible region powered by an invisible industry. For Central Appalachia, this invisibility relates to the region’s status as a resource hub for the rest of the world. The exploding mountains and buried streams of one extractive regime have been replaced by detention facilities. Both rely on the logics of extraction and disposal to operate. Both have long over-promised and under-delivered in Appalachia. Or, as Martin Arboleda describes it, the region operates as part of “a dense network of territorial infrastructures and spatial technologies”

The U.S. operates the largest archipelago of jails and penitentiaries in the world. And yet, it can be hard to find the prison in today's landscape. Prisons are, after all, by design and definition, spaces of disappearance. They disappear the people inside of them. And they are themselves increasingly disappeared from the dense social spaces where many of us live and move around.

In Appalachia, the immiseration of settler colonialism sublimated into the immiseration of fossil fuel infrastructure, and is now rescued by the immiseration of the prison-industrial complex. While the coal prisons of Appalachia are critical sites for understanding the relationship between settler colonialism, resource extraction, and racial capitalism, they are also critical sites in the fights for prison abolition, a just energy transition, and the realization of an internationalist Green New Deal. This is because the coal prisons of Appalachia teach us of the intertwined threads of colonialism, climate crisis, and racial capitalism–and to resist and transform these landscapes is to resist and transform its architects.

To fight the Climate Crisis, the built environment must be adapted from live to work to play. But to change the built environment alone (as Appalachia has exchanged coalfields from prisons) does not justice make–and to leave these changes in the hands of those who profited off building immiseration to begin with would be folly.