The border is in large part just an epistemology performed and materialized, a way of seeing and sorting that’s also, simultaneously, a mode of governing.

Today, there are 156,001 miles (251,060 km) of terrestrial transnational borders; enough distance to lasso the earth six times over.

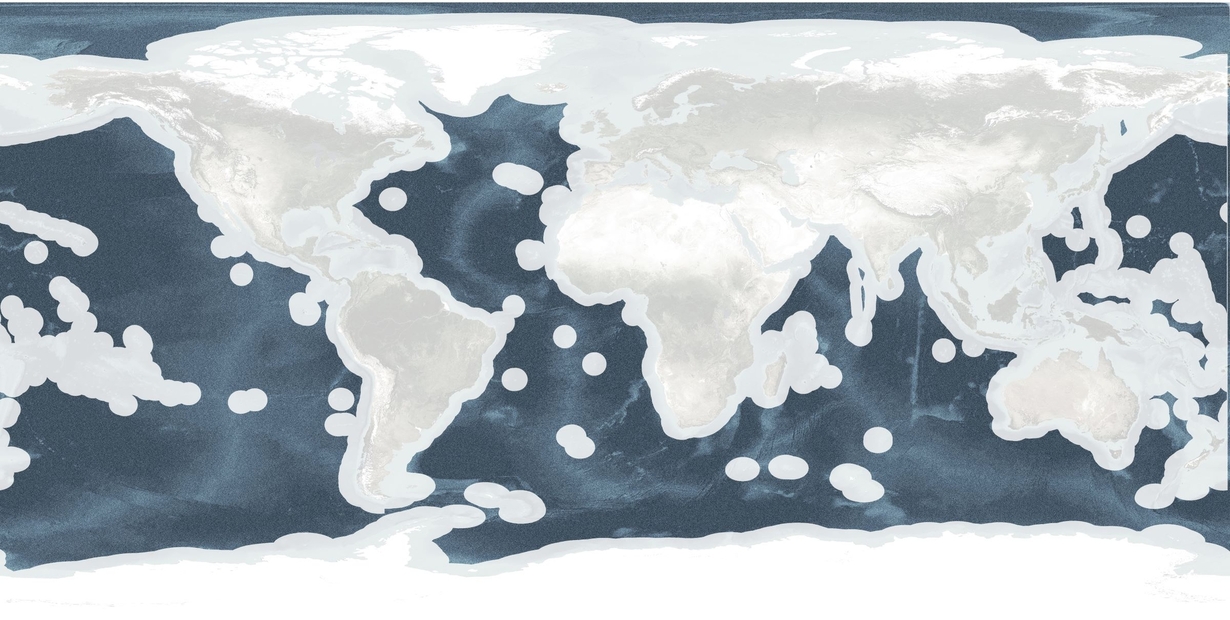

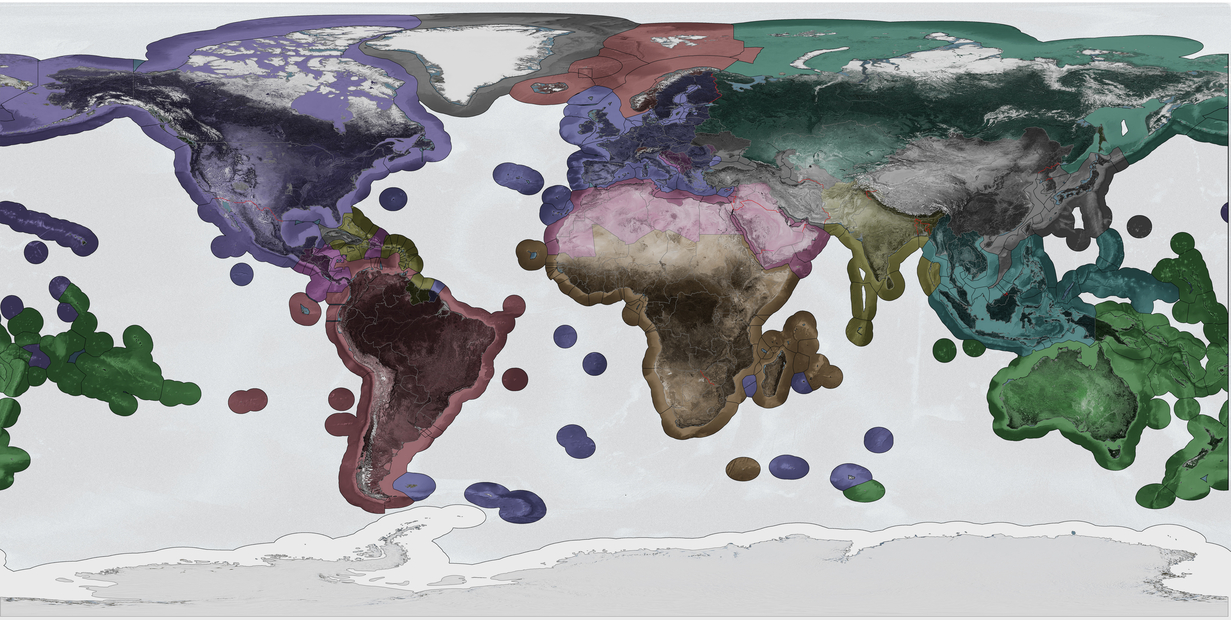

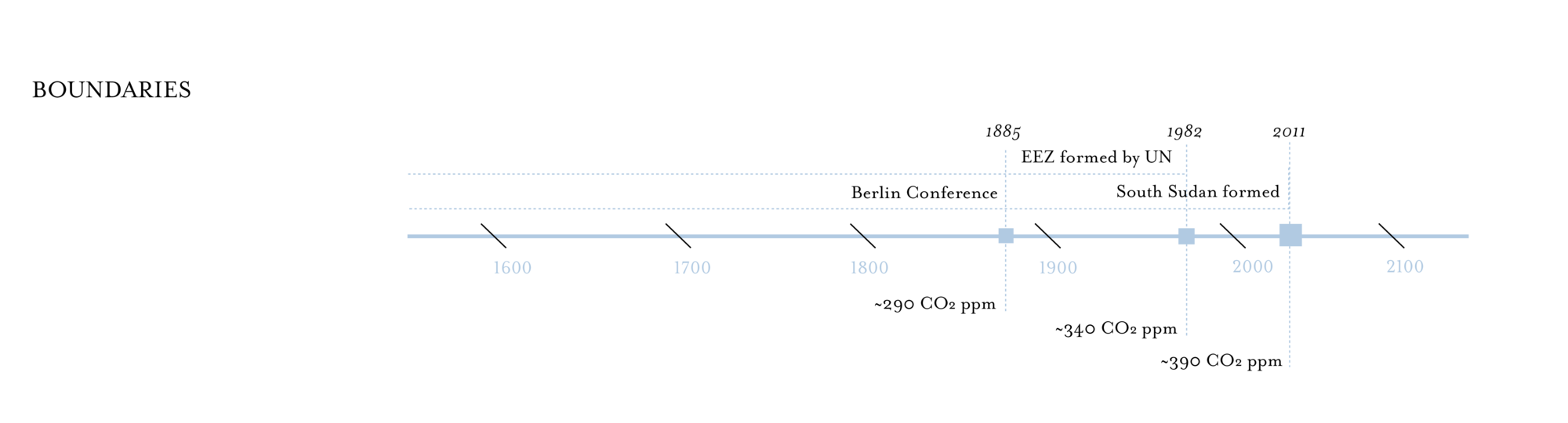

The map shows national borders and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundary, along with militarized borders in red. Countries are shaded according to their economic zone trading partners. In the alternate map, only the parts of the globe unburdened by borders, almost exclusively ocean, are shown in color while the land mass is highlighted by grey topography. The diptych highlights how borders shape the land and sea, but it also marks a moment in time, as borders are constantly in flux. The EEZ was only established in 1982, while South Sudan, the world’s newest country, was created in 2011. This image freezes in time the borders and boundaries that define this project’s scope of research. Part of capturing this moment in cartographic time, is recognizing, and mapping, places where claims of sovereignty are being made in an attempt to redraw existing boundaries, irrespective of their wider geopolitical recognition, including Palestine, Taiwan, Western Sahara, and unnamed disputed territories between several nations.

Border-making is central to the formation and maintenance of States, a notion that continues to undermine the effectiveness of global climate policy as each state jockeys for economic and resource dominance in the global political landscape. Currently, nation-state borders are defined by a state’s sovereign territorial hold, while nations with an ocean border are granted a 12-mile Economic Exclusive Zone.

The discreteness of the nation-state as container may be a potent fiction...Almost in spite of ourselves, the state continues to hold our collective political imagination.

Despite the considerable resources that go into border maintenance and militarization, the naturalness of borders, and the artificial distinctions they draw, borders are always sites of contestation. For a nation to have a contested border disputes is the international norm.

Mattern’s borderlands scholarship underscores two key insights for denaturalizing borders. First, borders are sites of social difference and contestation for an imagined ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ as defined by the State generally, and the nation state in our current political configurations. This line is etched into maps –and sometimes made physical in and on the earth–declaring definitively, according to the state, who belongs on this land. International attention is hyper focused on borders momentarily when the imposed differences bubble to the surface. Trump’s xenophobic and racist fixation with the US-Mexican border wall and his administration’s abhorrent treatment of asylum-seeking migrants highlight borders as explicit places of division, and as sites that can be leveraged to cause immense pain. Through the display of potential military force, hard infrastructural development, and xenophobic policy States are sending messages to foreign citizens and other States about their territorial power.

Secondly, borders are consistently remade and reconstituted through local conditions into different configurations of an ‘Us’ and a ‘Them’. Britain’s recent exit from the European Union and the pursuant closing of once open borders is one recent example. The countries within the European Union operate under an open border policy: given E.U. Citizenship, or the right stamps, people and goods can travel freely across the same line that would otherwise impede their movement throughout the European continent. These open borders expand notions of citizenship beyond the nation-state into larger coalitions that exclude at the continental rather than the national scale. This creates geographically nested identities tied to different scales of borders: someone can be both European and Italian. For Chenchen Zhang, borders are projects where open differences still arise in identity through the specific relations governing the whole and the individual members. In open border conditions, infrastructure often plays a key role in crossing these borders and in maintaining the identity of subgroups. As Zhang concludes, in her study of the Channel Tunnel connecting mainland Europe and the United Kingdom that, “the rationales, discourse, and organizing logics of bordering are also characterized by heterogeneity and contingency.”

The Climate Crisis, as an atmospherically mediated condition, confronts the traditional terrestrial notion of borders. Carbon burned anywhere and at any time on the planet directly contributes to the accumulative global effects of the warming planet, creating cascading effects that ignore drawn borders. Border making is a cartographic project, with lines drawn via international agreements and projection systems slipping and crawling awkwardly over real places. Increasingly flooding watersheds, stronger storms, wildfires, and droughts are real phenomena that are not bound by political treaties and geolocation frameworks. Border-crossing climatological events pose a serious risk to the traditional goals of establishing borders. Increasingly strong weather events damage property, disrupt livelihoods, and “waste” natural resources. These challenges alone have caused some nations to adopt the language of climate change as a threat multiplier, enfolding national security and militarization into responses to the Climate Crisis.

It is with this border-preserving logic that Field Notes begins its critique. Green policies that seek to wrestle the most benefits for a single nation is not Climate policy, it is domestic policy with the word green slapped on. The Climate Crisis is a global concern and Climate policy must strive to achieve global climate justice for all residents.