Injustice and oppression are global in scale. Why? Because Trans-Atlantic slavery and colonialism built the world we live in, and slavery and colonialism were unjust and oppressive. If we want reparations, we should be thinking more broadly about how to remake the world system.”

On July 14, 2020, then candidate Joe Biden released his climate plan: “The Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice.” The plan outlines a comprehensive set of policies and goals aimed at promoting clean manufacturing jobs, aggressively curbing pollution, addressing instances of environmental racism across the nation, and expansive investments in and deployments of solar and wind technologies. Republicans attempted to paint the plan as a rebranded Green New Deal while those on the left thought Biden should endorse the existing Green New Deal framework.

It might seem an odd place to start an essay on global climate justice with a climate plan by a single country, however, this is sadly the state of much of contemporary climate justice discourse and precisely Field Notes critique of the Green New Deal’s justice pillar: climate and environmental justice stops at the borders of nation states. This fractured configuration of both climate and justice paints today’s nations as the visionaries and arbiters of a globally-just future; a world which no doubt would maintain the economic and political supremacy of the Global North over the Global South. This is in large part because contemporary thought surrounding global justice is firstly, too focused on the nation state as a site of achieving justice, and secondly is based on redistributing social and economic goods (within and between nations) based on a specific moment in time. Political philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò calls this a snapshot view of distributive justice, that is “one that analyzes the appropriateness of the current distribution of wealth, resources and economic goods at any given moment in time.”

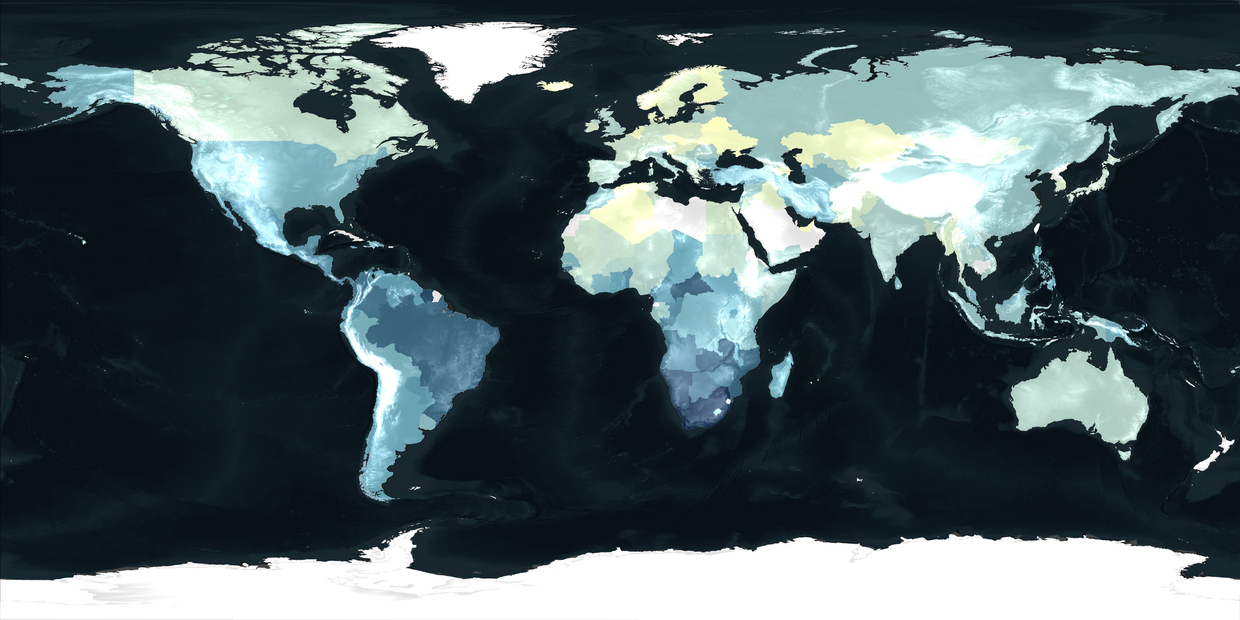

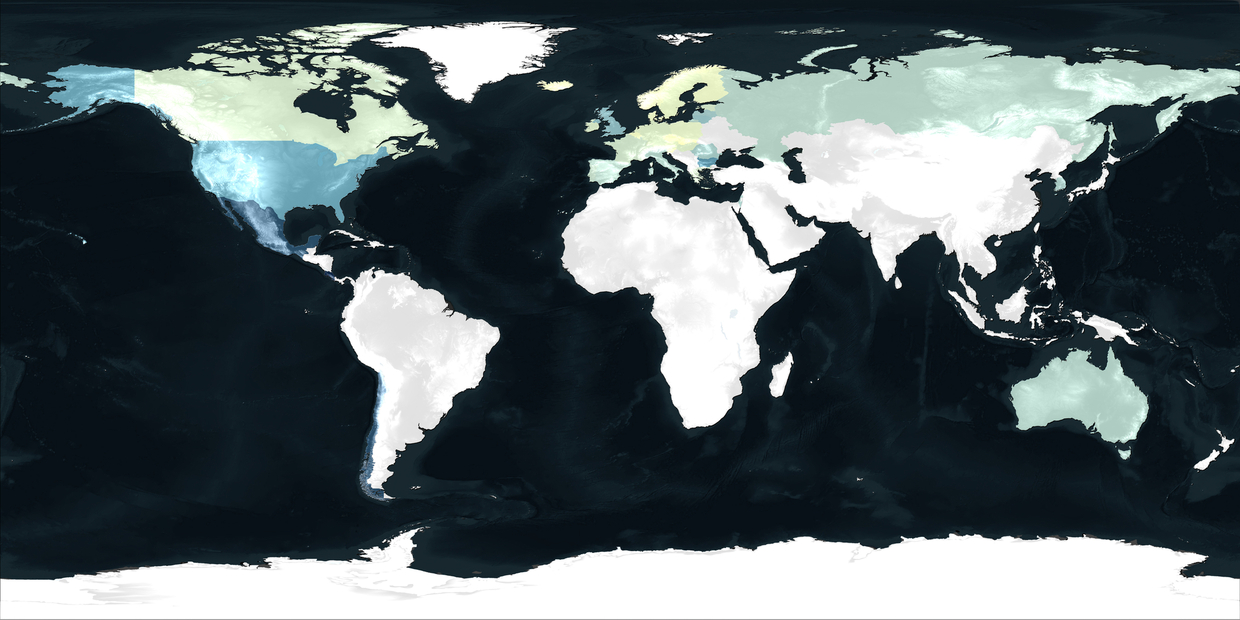

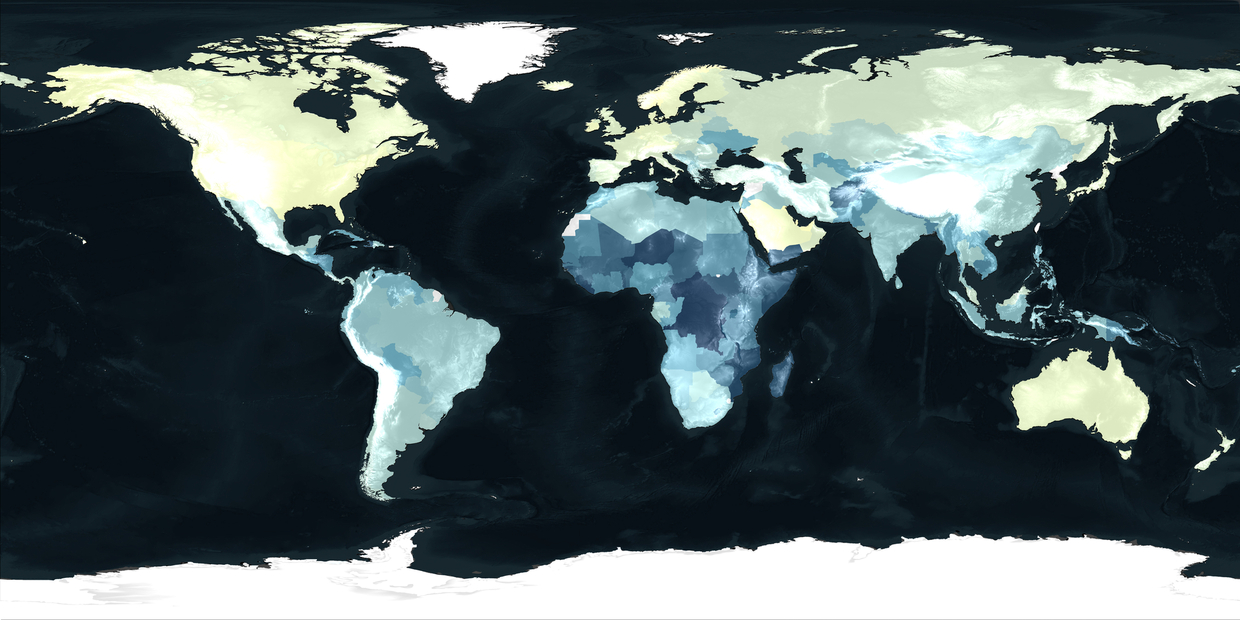

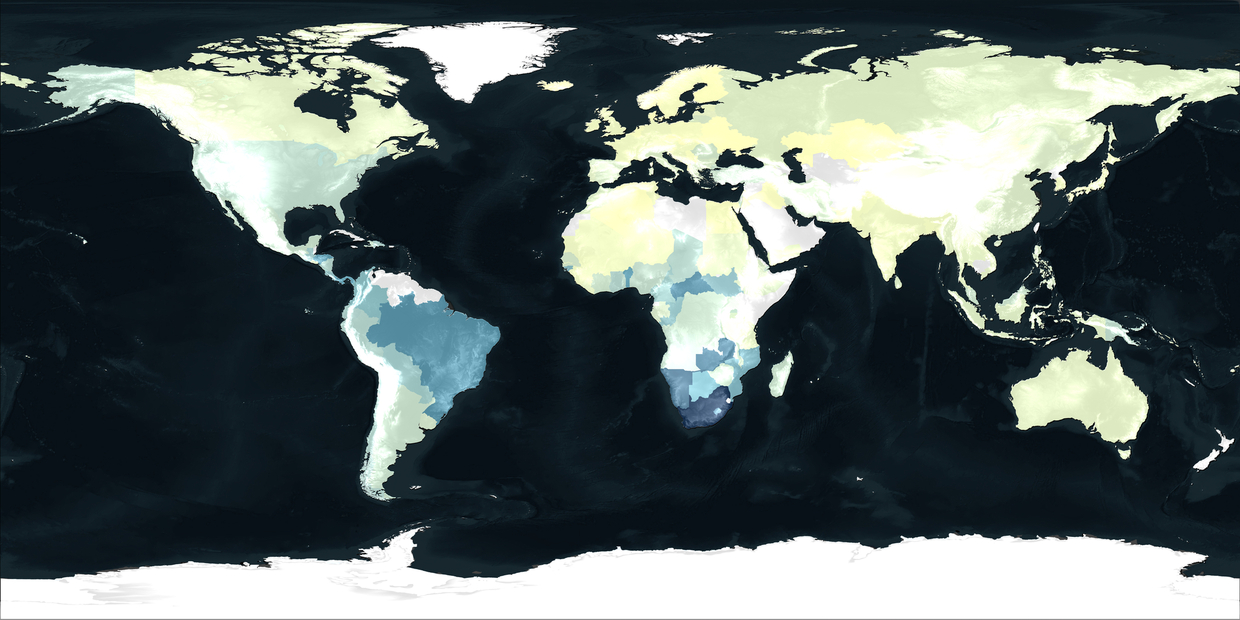

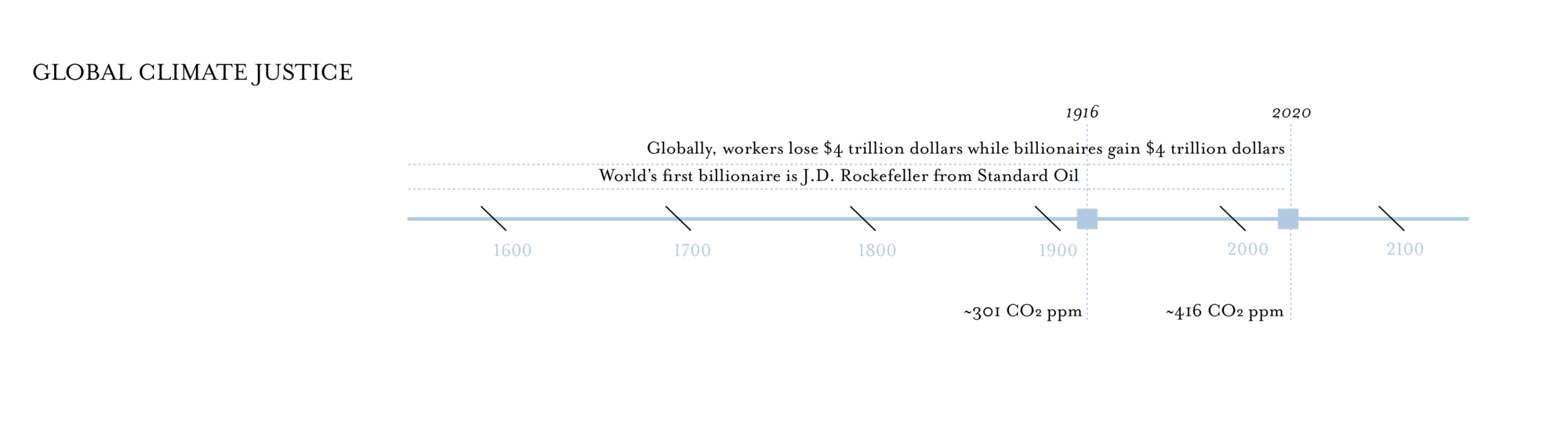

We must admit, the maps featured along this essay operate under the snapshot view of distributive justice. The maps featured below, themselves, present a moment in time in which to address injustice. Each index is representative of today’s global distribution of income, cartographically delineated as geographies for NGOs, intergovernmental banks like the IMF and World Bank, and foreign investors to promote new economic opportunities for nations and peoples. Furthermore all four major indices of global justice (GINI index, the Palma Ratio, the Income Index derived from the Human Development Index, and the quintile ratio of income inequality) are measures of income. The contemporary language of global (in)justice is economics.

In shades of blue and yellow, multiple measures of economic inequality are projected across the globe. The four measures are the GINI index, the Palma Ratio, the Income Index derived from the Human Development Index, and the quintile ratio of income inequality. Each ratio or index, by virtue of its specific calculus, tells a different story about the global distribution of income inequality. We ask: how can something which so concretely defines billions of lives be so hard to capture?

Not captured by the focus on economic factors of inequality are myriad social and material formations that must be rethought as the new conditions for a base standard of global living which focuses on assuring the best quality of life for as many people as possible. A focus on solely economics posits a world in need of repair and a world of sacrificed territories and peoples, ignoring the potential of a new, just future to be imagined, and won.

The economic stranglehold of justice discourse is perhaps most evident in contemporary discussions of reparations, which often focus on one-time monetary payments that aim to cleanly resolve past injustices. Reparations, in the broadest sense, are meant to rectify a wrong; they are a means of achieving justice. Often, reparation schema are bound by legal systems, limiting their geographical and historical reach. Throughout history attempts at codified systems of justice have ranged from the potentially violent Babylonian maxim of an ‘eye for an eye’ to the sprawling, privatized, carceral empire of the United States today.

In the case of historic oppressions, parties and actors in the wrong might seem clear, for example the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation producing Redling maps for 239 American cities that categorically denied homeownership to Black citizens. But, these institutions were empowered by a Jim Crow friendly federal government. Establishing blame is complicated by asking who is ultimately responsible for the injustice of redlining: Cartographers who created the maps? The institutions themselves? Congressional representatives that created these institutions? What is clear through the fog of blame is that the federal government commissioned a cartographic practice that has resulted in nearly a century of economic injustice as generational wealth building was denied to thousands of Black citizens in the late 1930s. The city of Evanston, a suburb of Chicago, enacted a harm-based reparation program in 2021, offering $25,000 grants to qualifying Black residents for home repair, down payments, or other housing related needs. Eligibility was dependent on homebuyers or a direct ancestor being an Evanston resident between 1916 and 1969, or upon showing evidence of housing discrimination from Evanston policies.

Táíwò is one scholar seeking new forms of enacting global climate justice. At the core of his critique, Táíwò takes issue with the harm-repair model of reparations. He argues that typical models of reparations have focused on addressing historic injustices as instances of harm, which, coupled with the unfolding futurity of the Climate Crisis, are no longer morally applicable or effective means of ensuring climate justice.

Instead, Táíwò argues for a constructive idea of reparations, focused not on harms committed, but on the level of global well-being we wish to achieve.

Will we welcome people who flee submerged coastlines and sinking islands–or will we imprison them?”

The materialist formulation of cosmopolitanism, which is the collection of beliefs that illustrate the philosophical and social implications of being a citizen of the world, is significantly expanded from the contemporary dignity-based focus of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism was first formulated by Greek philosopher Diogenes the Cynic, who in response to the unequal application of justice based on social status, declared himself a cosmopolitan, a “citizen of the world.”

Despite the weakened inclusivity of Cosmopolitanism, it remains the bedrock for discussing, organizing around, and legislating global justice. Political philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum notes that the Cosmopolitan position, thanks to its reverence within Western thought, has been adopted (and adapted) in the formation of many human rights campaigns, national constitutions, and international agreements, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The impact of place on someone’s capabilities is far more granular and nuanced than nationality alone. As the groundbreaking work of Dr. Robert Bullard, known as the “father of environmental justice,” has shown, the distribution of pollutants and toxic materials follow lines of race and socio-economic status within the United States.

The Climate Crisis is an inherently material phenomenon. Abstract concepts like dignity or honor do little to stop hurricanes, forest fires, storm surges, famine, or drought. The focus on dignity is in acute misalignment with Climate Crisis-induced resettlement that will occur across the 21st century, which will put immense strain on existing agricultural production systems. Peter Kropotkin in the late 19th century foresaw the mismatch between ideals and the material needs of people: “It has always been the middle-class idea to harangue about ‘great principles’ –great lies rather! The idea of the people will be to provide bread for all.”

It should be made clear here that Nussbaum’s position differs diametrically from Kropotkin. She does not argue for overthrowing the existing governance system, instead she argues that the focus of aid must be on ensuring peoples everywhere have institutions which materially provide for their basic needs.

Naturally, much of contemporary Global Climate Policy has focused on the exact aspect of cosmopolitanism Nussbaum critiques: the focus on opportunity over capability. The World Bank and IMF focus on bolstering under-developed economies, not ensuring the material improvement of people’s lives around the globe.

These new means are climate reparations: future-oriented redistributions of wealth, social goods, and resources which pointedly aid those who have been burdened by the accumulated disadvantages of a racialized, colonial world.

Maxine Burkett, the scholar who coined the term Climate Reparations in 2009 in her eponymously named article, argues that the unequal geographic, and subsequently economic, effects of the Climate Crisis reveal an imbalance between carbon emitters and those most directly affected by the Climate Crisis.