When considering the Arctic future we must come to terms with its status as a highly covetable chamber of natural resources that sooner or later will be extracted, with great ecological consequence for both the local and global environment. While the mechanisms behind the decision making affecting the future of the Arctic are a complex network of powerful ideological, economic and not least the geopolitical agendas, we need to recognize the role of the Arctic imaginaries in fueling these agendas.

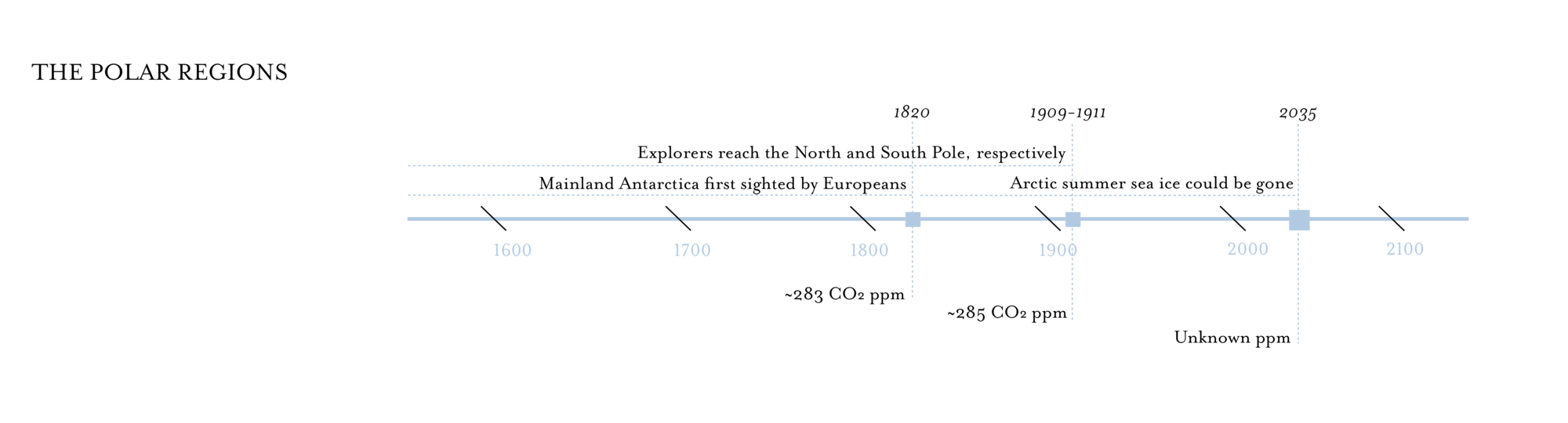

The polar regions are among the planet’s most complex political ecologies. As an assemblage of territorial resources and imaginaries, the Arctic and Antarctic have been imbricated in global population and resource flows for millennia. Well before the peak age of polar exploration began in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries, ideas of travel to the stark, monochromatic landscapes of the Far North persisted. As early as the third century B.C., Greek tales of the mysterious northern island of Thule (generally believed to be Iceland) animated the folklore and mythology of Western empires. The early modern period was also replete with competing visions of Arctic utopias and dystopias, each extending the imaginary of Greece’s Thule intoa new century’s shifting geopolitics.

In the sixteenth century, the Zeno Brothers mapped and described what was later revealed to be a fictional excursion to Alba—a small city in the stark moonscape of Northeast Greenland they described as “an educated utopia on an island of plenty.”

Since the mobilization that accompanied World War II, the idea of Thule has been thoroughly militarized. It became synonymous with the American military’s installations and base of operations in far Northwest Greenland and, as a result, is now a key strategic node in the ongoing militarization of the greater Arctic.

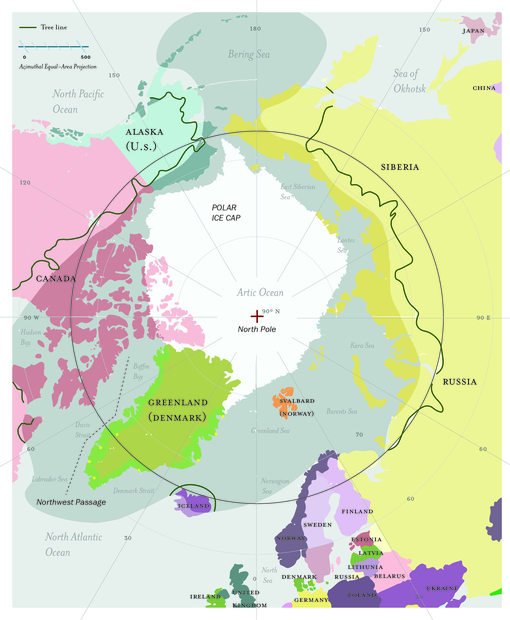

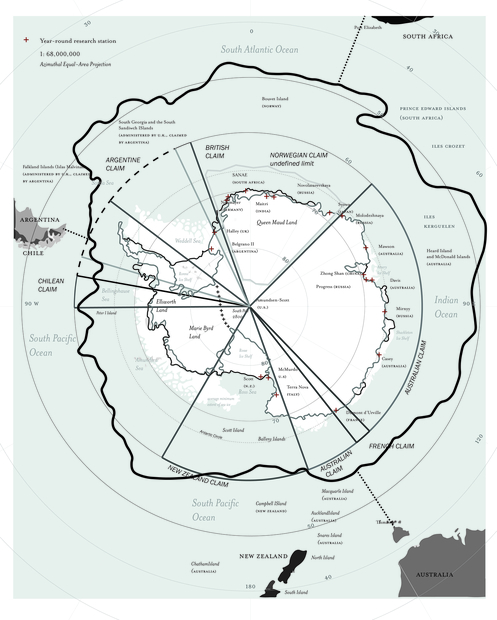

In this pair of maps, overlapping definitions of the North and South poles are presented. Each pole, and the region that has come to define it cartographically, does not have clear cut borders; no single government to draw a boundary line through the slurry of sea ice. The diptych contests what constitutes a “polar region”, especially when both poles are defined by overlapping, messy, and often conflicting characteristics from competing national claims, to shifting sea ice, and the promises of continued and future extraction.

The Polar Regions are broadly delineated geographic territories within which multiple competing conceptions of what it means to be “polar.” Yet these ideas are in ever-ceaseless flux. Where does the Arctic begin? Where does it end? What does it mean to be of or in the Arctic? The answers to these questions are just as much geographical as they are political. Arctic, etymologically, comes from the ancient Greek, roughly translated to “of the bear”, referring to the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor (the Big and Little Dippers, respectively), two of the most recognizable constellations in the sky in the Northern Hemisphere. Similarly, Antarctic quite literally means, “not of the bear”, the inverse, the negative expression of the Arctic. These metaphors, now naturalized as part of a common geographical discourse, illustrate how the long history of human migration and celestial navigation has shaped ideas about the Polar Regions and how these ideas have subjectively changed over time. One of these concepts is that of the Arctic and its antonym, the Antarctic. In this conception of polar, the Arctic and Antarctic are not places per se. Rather, they are ideas about what constitutes a place—its geographical delimits, its cultural and political economic cohesion, and its physical and geologic characteristics. This includes things like the expanse and attributes of rock and ice, the people who live amongst it, and the flora and fauna that traverse its landscapes. While these things each materially exist in the polar regions, they are not, in and of themselves, entirely constitutive of what is broadly construed as the Arctic.

These ideas vary widely depending on context. Ecologists delineate Arctic ecosystems as beginning beyond the northerly latitude where boreal forests give way to the tundra, a timber-line that meanders unevenly across the greater North. Cartographers, on the other hand, may designate the Arctic or Antarctic as any region inside the Arctic or Antarctic Circles, the respective latitudes at which the sun does not rise for one full day of the year. Yet, Arctic and Antarctic ecosystems spill over well past these rather arbitrary circles. For example, a majority of Iceland lies below the Arctic Circle, and yet the entire island is considered an Arctic ecosystem. In the case of Antarctica, a more ecologically accurate boundary might be the Antarctic Convergence, a shifting, semi-porous boundary where warmer waters from the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans meet the cold waters of the Southern Ocean (see map). However, this thermal convergence is not a hard boundary, is in constant flux, and at any given time can be between twenty and thirty miles wide. It is also shifting, often unpredictably, as the planet warms and ocean chemistries change.

The Arctic is also defined as a “knowledge space,” or an “interactive, contingent assemblage of space and knowledge, sustained by social labor.”

In any age, at any given moment, there are many Norths, insular ideals, and peripheries.

The Arctic and Antarctic are also defined by political constituencies and competing land claims, artifacts of the long histories of colonialism, exploitation, and violence exported across the planet. Global warming is rapidly dissolving long standing ecological markers of the Arctic (such as permafrost, Summer sea ice, and glacial ice). This thawing is surfacing old forms of colonial violence, and manifesting new ones, as Arctic and sub-Arctic nations around the globe begin to reassess what the Arctic means for the future of global logistics, energy independence, and national security. These reassessments are taking many forms. In April of 2021, Greenland (a majority indigenous nation that remains a colonial territory of the Kingdom of Denmark) held a controversial snap election

The bounds of the Arctic are not, and never have been static. The region is composed of a plethora of diverse landmasses, Indigenous populations, national claims and interests, logistical entanglements, and overlapping political and social boundaries.

The language of the “frontier” is in direct opposition to the much more long standing and legitimate land claims of the indigenous Inuit, who hold political representation not as states, but only as “permanent members” of the Arctic Council, through organizations such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council. There are currently no fully autonomous indigenous Inuit states, the two closest being Greenland and Nunavut. Similar to Greenland, the indigenous territory of Nunavut was created in 1992, and even though it has its own independent government, it remains a territory of Canada. If Greenland achieves independence from Denmark, it will be the world’s only fully autonomous, majority-indigenous nation state.

New claim-making will only increase as the chaos of planetary climate change worsens and conceptions of the bounds and definitions of the Arctic and Antarctic continue to shift—or be shifted by opportunistic nations aiming to parlay the melting regions into a strategic geopolitical outpost. Yet ideas about these regions have rarely ever remained stable, and any framework for an international Green New Deal must align itself with this fluidity, while also contending with how the polar regions continue to be defined and redefined to fit particular strategic ends for prospective futures of resource extraction and national security. Additionally, it must move well beyond the objectives and desires of nation states, and find ways to build sustainable futures in deep collaboration with the indigenous Inuit of the Circumpolar North. This starts with acknowledging that the Arctic and Antarctic, as discrete geographies, do not exist. They are called into being—made to exist in particular ways by people with specific interests.