Just as teams compete to be champions, so states compete for security. And just as the champion is better at playing the game than other teams, so states with more security than other states are better at playing the neorealist version of the ‘game’ of international politics.

In 1048 CE, the Yellow River poured over its banks and out across the Hebei Plain. Its surging waters swept across farming communities, coursing through crops and homes in search of the Pacific Ocean. The riverbank’s breach gave rise to a deltaic system that stretched more than 700 kilometers at its widest point, reshaping the region’s physical and social geography along the way. This event is the focus of Ling Zang’s The River, The State, and The Plain, an environmental history of the Song Dynasty and its role in constructing the Hebei Plain and Yellow River system as we know them today.

The Song Dynasty, formed in 960 CE, was struggling to engage with the then-independent region of Hebei.

Prior to these interventions, the Yellow River served as a natural barrier between the Hebei Plain to the north and the heart of the Song Dynasty in the south, the Henan Province. The river’s hydrology pushed floodwaters to the South, leading Song emperors to propose a series of infrastructural schemes for restructuring the region’s hydrologic systems around flood mitigation. In building out these visions, they went so far as to divert the river to the north when it shifted course during a flood event that threatened to inundate much of the Henan Province. During the flood, most observers believed it was the natural outcome of a large river dealing with a generational storm event. But Zhang punctures this myth, showing through archival work that the severity and frequency of Yellow River floods during this period were made worse, if not created altogether, by the Song Dynasty’s efforts to control and otherwise manipulate the river.

For the next eighty years, the Yellow River would resist the various attempts at control led by the Song Dynasty. It still flooded regularly, draining considerable wealth from the Song and triggering a migration crisis in which more than a million Hebei refugees fled the once-autonomous and highly productive agricultural region.

The strain of managing a fiscal and refugee crisis eventually became overwhelming. It led Song rulers to pursue an often indecisive policy of flood management, resettlement, and economic growth that, by most measures, failed spectacularly. In their attempts to create a secure buffer zone that could limit military conflicts and bolster their food system, the Song rulers treated the Hebei Plain as a sacrifice zone—a place to be flooded and otherwise manipulated in the service of imperial expansion.

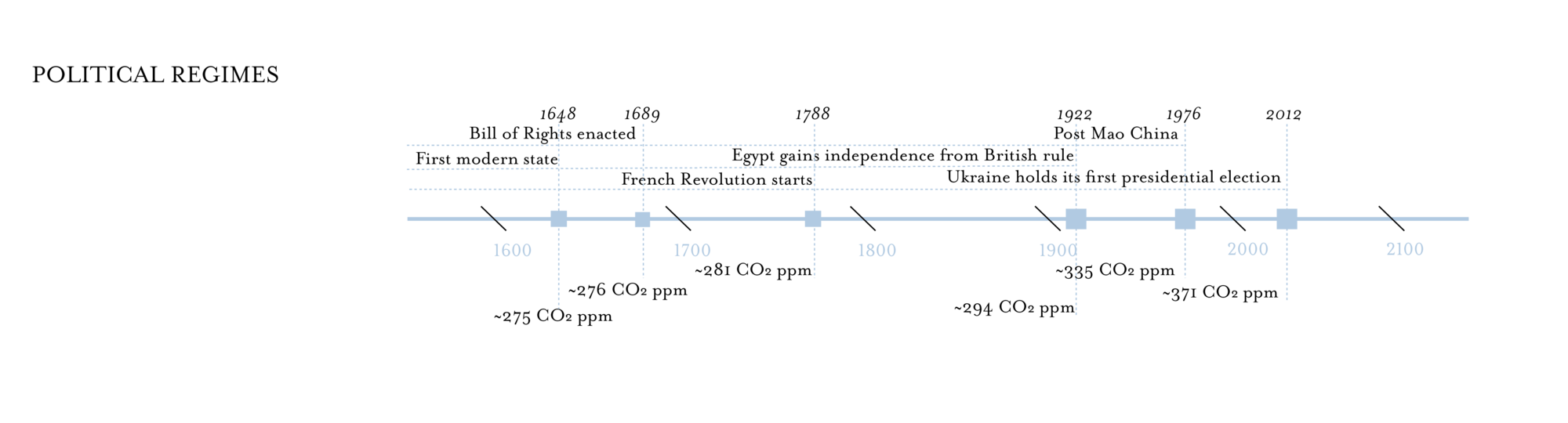

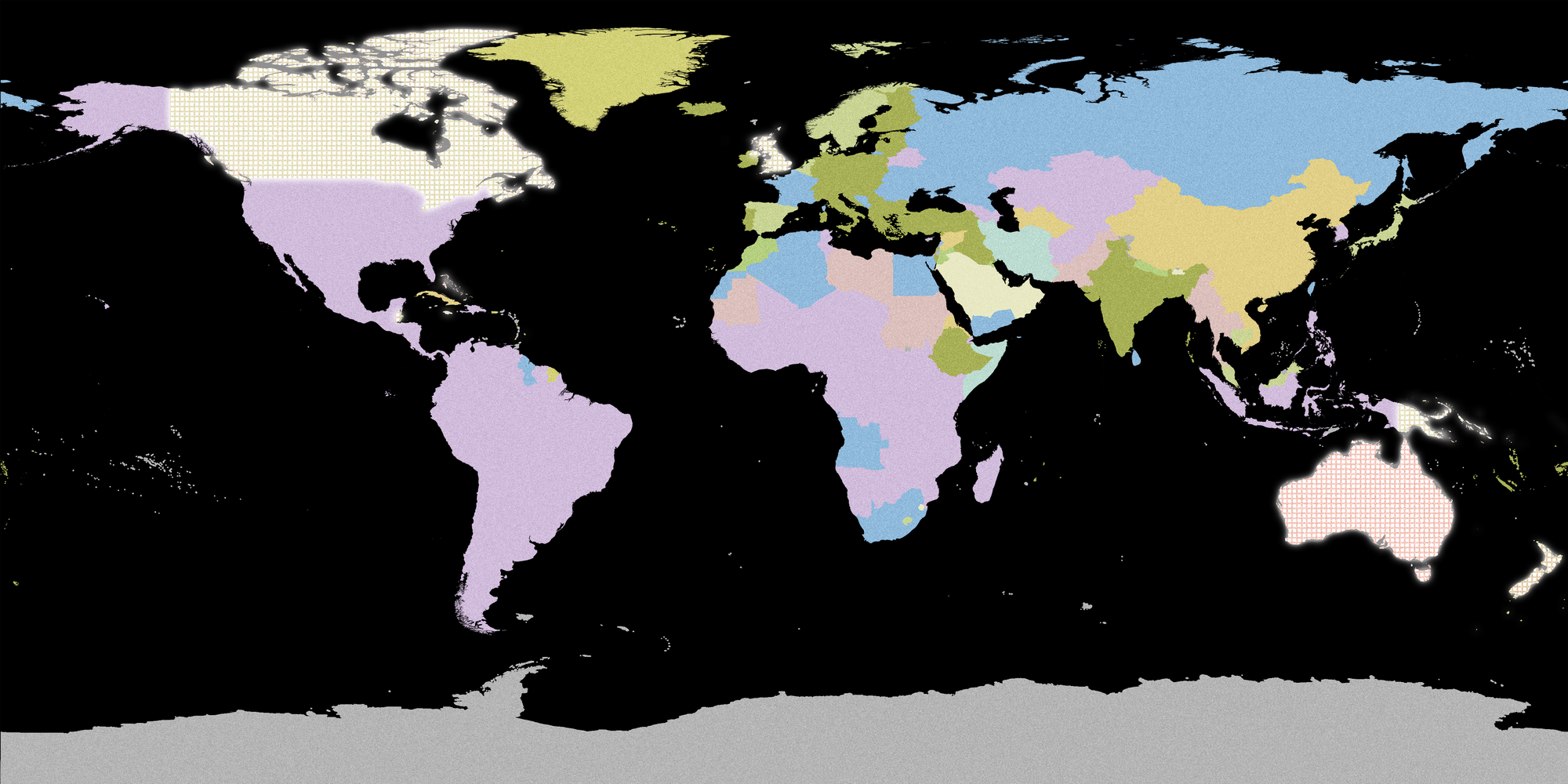

Governance systems are highlighted in pastel colors over a black background. Commonwealth nations, nations that have chosen to remain, at least symbolically under the rule of the British monarchy, are called out with a glow and hatch.

This map shows the distribution of different types of governance across the globe. Our interest, here, is not to make claims of an ideal governmental structure for the globe or to offer a snapshot of the frightening trend towards far-right governments, but to contest the reliance on the nation-state as a means to develop, enact, and fund ventures to dampen the Climate Crisis. National governments, regardless of governmental structure, have sought to ‘win’ climate negotiations, securing their ways of life, and by extension economic supremacy. An obsession with political jockeying will do little to meaningfully benefit the billions of lives subject to the effects of the Climate Crisis. Here, boundaries are removed from the nations to project a world without them, a world focused on lifting up the global citizenry over those found within invented lines on a map.

Though this interlude is obviously focused on a particular moment in the Song Dynasty’s rule, it is far from the only example of state-led interventions in political, economic and ecological systems that produced far greater crises than the ones that precipitated their development. Contemporary political regimes, often rooted in nationalistic and autocratic rule, tend to reproduce the dynamics that shaped the Song-Hebei relationship. From the “America First” and “Buy American” rhetoric of Donald Trump and Joe Biden to the “Exceeding the UK, Catching the USA” (超英赶美)of Mao Zedong, the practice of identifying common enemies, deeming certain people and regions as expendable, and delineating a clear and militarized border than can be defended is nearly synonymous with statecraft in the 21st century. Daniel Conversi describes this rise of nationalist politics across the planet as rooted in a need to construct oneself “against another external Self, an outside community lying beyond national boundaries without which the very definition of nations remains challenged and challengeable.”

These state-led projects of securitization and control—of people, ecological systems, and resources—have also bled into local, national, and global climate politics. Attempts to create global climate plans, such as the Paris Agreement (2016) and the Copenhagen Accord (2009), have thus-far been non-binding, meaning there are no enforcement methods, no stick to the carrot of climate mitigation.

Even plans developed beyond the organs of the state have largely failed to transcend these challenges. The Great Green Wall, meant to stop the continued desertification of sub-Saharan Africa, is perhaps the starkest contemporary example of such a plan—an archetype of what Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, following Doreen Martinez, refers to as climate colonialism.

Now geoengineering promises possibilities for providing the conditions that allow the perpetuation of fossil fuel powered neoliberalism further into the future. Or rather it might, if security continues to be formulated in terms of the perpetuation of the existing political order, precisely the order that has generated such dramatic ecological disruption in the first place.