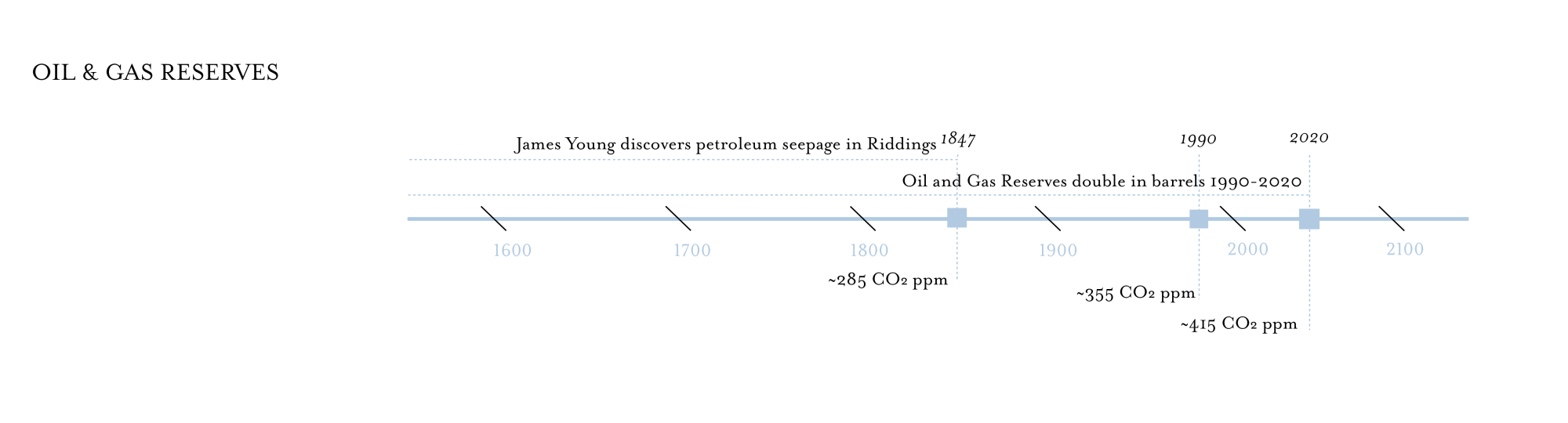

The problems of peak oil and climate breakdown are connected, as both arise from and threaten the modes of social life created using fossil fuels.

Much of the global energy system is organized around a set of relations, speculations, and operations tied to subsurface deposits of oil and gas often referred to as “reserves.” But what, precisely, is a reserve? Oil and gas reserves are not merely passive, subterranean deposits beneath the surface waiting to be discovered, exploited, and converted to fuel. Rather, they are assemblages of knowledge, technology, and political economies that are actively and purposefully constructed in order to imagine and maintain a complex of interests bound up in the burning of fossil fuels.

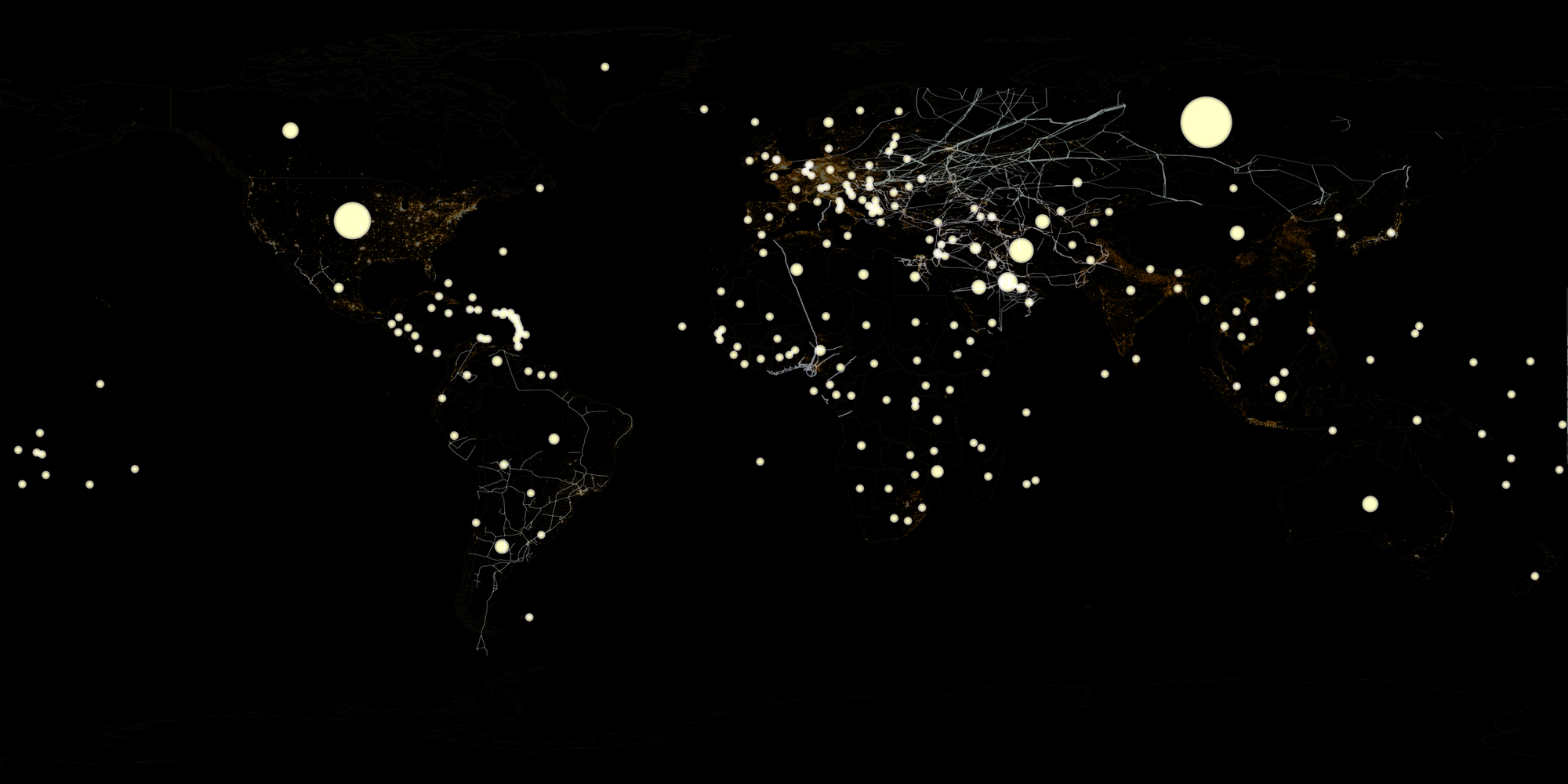

We refuse to map oil and gas reserves as a cartographically precise set of extractable resources that oil executives, policy makers, and governments can organize and create political economies around. Continued speculation over fossil fuels is antithetical to an internationalist Green New Deal. Instead, expected technically recoverable quantity of documented and expected future reserves are mapped loosely to individual countries alongside the transnational network of built or planned oil and gas pipelines. A base map of global GDP without national borders or a land/water distinction highlights the role of capital in strategizing and mapping reserves as a commodity.

The concept of a reserve and its embedded resources implies a kind of static, unidirectional relationship.

The movement from Oil-in-place to proven reserves is fundamentally a knowledge practice, underwritten by massive investments in research and development for new extractive technologies intended to transcend “thresholds of detectability”.

Peak oil is not so much a geological problem as a political one, more reflective of the contemporary economics and technologies of detection than of the oil itself. As such, peak oil crises often presage expansions of technologies of detection and extraction, and geographical reorganization of the industry. After the peak oil crisis of the 1970s, the political economy of the industry reorganized around newly detected oil fields in the Middle East. The early 2000s saw similar anxieties, and brought with it the hydraulic fracturing boom in the United States.

Geology is a relation of power and continues to constitute racialized relations of power, in its incarnation in the Anthropocene and in its material manifestation in mining, petrochemical sites and corridors, and their toxic legacies—all over a world that resolutely cuts exposure along color lines.

If an internationalist Green New Deal is to be successful, it will have to move beyond supply side demands to keep fossil fuels in the ground, though doing so is clearly a necessary, if insufficient, aspect of such a program. Its program must also question the idea of the reserve—a concept that, at its core, is more than a spatial variable or indicator. In the global energy system, reserves represent an ordering logic that shapes ownership over and profit from resources, creates and maintains new forms of commodification, and naturalizes the kinds of extractive supply chain capitalism and geographies of extraction described in Martin Arboleda’s Planetary Mine.

As with oil and gas extraction, vast geographies across the Global South are being organized for mineral extraction in service of the energy transition. Indigenous communities bear the brunt of these processes. From the rampant droughts on indigenous lands due to water-intensive lithium extraction in the Atacama Desert (one of the driest places on Earth)