A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. The only value in our two nations possessing nuclear weapons is to make sure they will never be used. But then would it not be better to do away with them entirely.

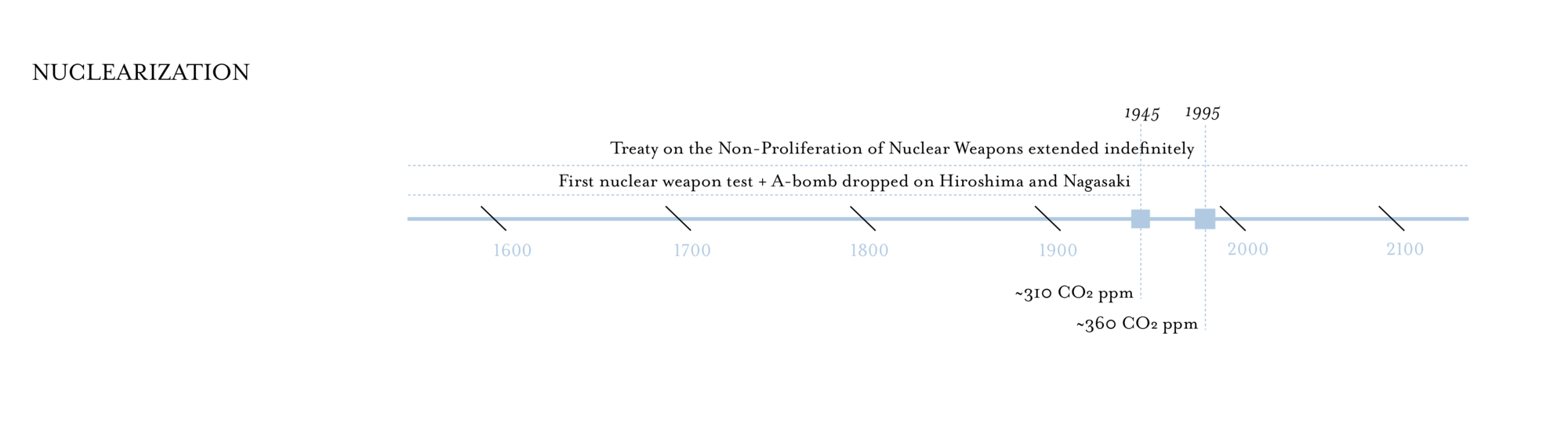

July 16th, 1945: The date of humanity’s nuclear awakening. It is, without equivocation, a day that made the world considerably worse. Rooted in a form of techno-utopianism that now extends into the ideology of ecomodernism, the advent of nuclear weapons gave rise to a global path dependence forged by geopolitical conflict, mass militarization, and an energy transition. The nuclear age quickly became one of promise—that of abundant low-carbon electricity—and of peril—that of a nuclear war that could threaten humanity’s existence.

But a few weeks later, long before those political and economic transformations became manifest, the first and only two atomic bombs—nicknamed the “Little Boy” and “Fat Man”—ever deployed in war were dropped by the United States military on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. More than 100,000 civilians died instantly, and hundreds of thousands more would become casualties over the weeks, months, and years that followed, as their radioactive exposure corroded and destroyed their vital organs and biomolecular systems.

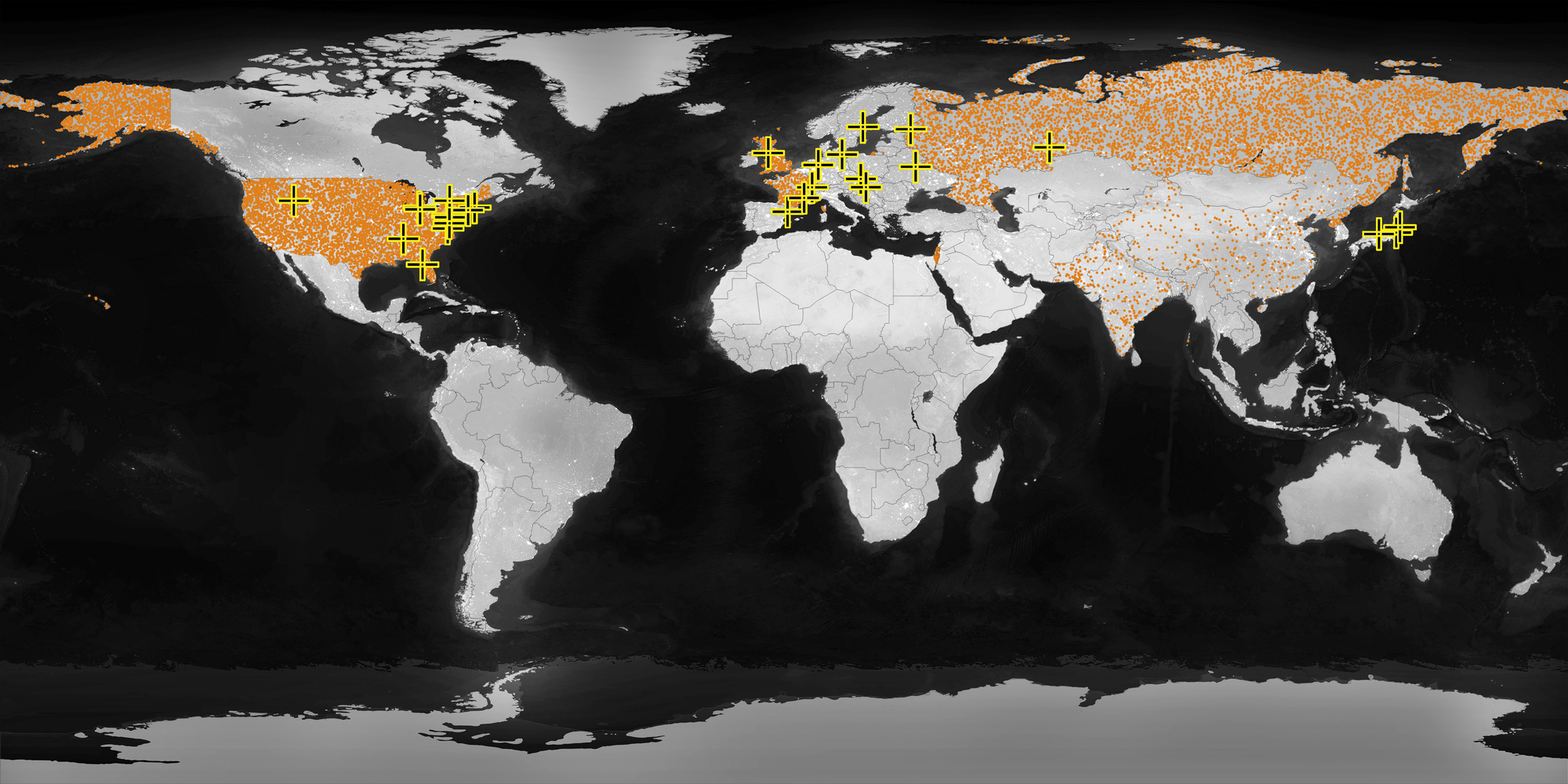

By the time Japan surrendered on September 2nd, 1945, the US possessed only a single viable bomb in its nuclear arsenal—at the time, the only nuclear weapon of any kind left on the entire planet. Today there are 13,389 nuclear warheads in the world. 3,750 of those weapons are held in a constant state of readiness, able to be launched within moments of a Presidential order. Of the 195 nations in the world, only nine possess nuclear warheads: The United States (5800), Russia (6375), China (320), France (290), UK (215), Pakistan (160), India (150), Israel (90), and North Korea (30-40).

There are nine nations that have a nuclear warhead arsenal: China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, The United Kingdom, and The United States. Here they are mapped with a geographically distributed display of their total existing warhead count. In the 1990s, Russia and the US agreed to decommission large portions of their respective existing nuclear stockpiles, but unratified international treaties have failed to prevent the development of new nuclear warheads. Sites of nuclear testing, warhead deployment, nuclear accidents, and nuclear waste spills have been sites of potential radiation exposure and have historically harmed Indigenous peoples at higher rates. Geolocated data for nuclear warhead deployments and testing was not available to the project team, but sites of nuclear accidents are shown here with yellow and black crosshairs.

Throughout the Cold War, mutually assured destruction became epistemic—equal parts a deterrent for war and a driver of the expanding military industrial complex. Power was measured in number of active warheads and nuclear yield, the measure in tons of TNT of explosive might. Both metrics massively ballooned throughout the later half of the 20th century as the US and the USSR sought to ensure maximum striking potential in event of a nuclear attack. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima was 15 kilotons. 16 years later, the Soviets would produce the Tsar Bomb, officially known as ‘Item 106’, with a yield of 57 megatons; 3,800 times more powerful than the bomb used to destroy Hiroshima.

The world is still seeking ways to dismantle these artifacts of the nuclear age. Demilitarizing through nuclear de-escalation and disarmament remains a key aspect of geopolitics between nuclear countries: the most recent nuclear armament treaty between the US and Russia, the 2010 New START Treaty, limits the active number of warheads each country can own to 1550.

For billions of people around the world, the fear of a nuclear attack never came to pass.

Drawing from the tragic lessons of nuclear atrocities experienced by the Indigenous Peoples, we recognize that the testing, development, and use of nuclear weapons is a crime against all humanitarian law...

Escalating fears of radioactive particles raining down from the sky, poisoning the oceans, and altering the upper atmosphere across territories well beyond the designated testing sites resulted in the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (PTBT, sometimes referred to as the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT)). The PTBT explicitly banned all nuclear testing that didn’t occur underground in an attempt to stop radioactive particles from entering the atmosphere, oceans, and space.

With the PTBT establishing a precedent for international agreement, nuclear testing bans spiraled into a series of bookmarked limits on testing sites: no nuclear testing or storage on the moon and other celestial bodies; no nuclear testing in Antarctica; no nuclear weapons in Africa or South East Asia. Finally, in 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) would be adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, but still has not been officially signed and ratified by the requisite number of member nations to go into full effect. The United States has signed, but not ratified the treaty, but thus far has honored the terms despite its unofficial recognition. A key provision of the treaty was to establish a global monitoring system to detect nuclear tests by tracking seismographic records, oceanographic sounds, and measuring for particles that have higher than normal levels of nuclear energy.

Environmental activists have shifted their focus from global catastrophes and atmospheric radiation to the harmful effects of sites in which the mining, transportation, development, and testing of radioactive materials occurred. The threat of nuclear attacks from abroad often occluded the nuclear poisoning brewing at home. For example, Hanford Nuclear Site in Eastern Washington in the US has been threatening the groundwater for nearly 70 years. Paul Koberstein, in “The Sacrifice Zone”, details the purposeful wasting of this site, rendering the landscape an uninhabitable zone both before and after the catastrophic spill.

The 1951 spill, and its relatively (to the lifespan of radioactive material) immediate effects are incomprehensibly small in comparison to the 346 billion gallons of contaminated waste produced by the five plutonium-processing plants. Furthermore, the waste produced there is not the only waste stored on site. Hanford accounted for “more than 80 percent of [the US’s] highly radioactive spent reactor fuel, almost 60 percent of its high-level radioactive wastes, more than half of its buried "transuranic" wastes (elements heavier than uranium), and the largest amount of contaminated soil and groundwater.”

Nuclear exposure occurs throughout its entire lifespan, from mining to production, to testing, and, most precariously, to storage and alongside many other issues of environmental justice tends to more readily endanger Black and Indigenous peoples. In a presentation on NativeAmericanScience.org, Ray Pierotti outlines how nuclear storage has been foisted onto indigenous tribes all throughout the United States, comparing the nuclear waste to a contemporary form of the colonial era chemical warfare of gifting a blanket covered in smallpox.

Testing and storage sites are places of ongoing occupation. These sites are ravaged and sacrificed on time-scales outside of our ability to take care of them, causing potential harm for generations to come. Nowhere is this more clear than in the United States relationship with Indigenous peoples. The authors of the Red Deal, call for the “End of Occupation Everywhere” going onto identify the source of US military presence globally as the “creation of US settler sovereignty, forged through war against Indigenous nations.”