On one side of the paradox, megaprojects as a delivery model for public and private ventures have never been more in demand, and the size and frequency of megaprojects have never been larger. On the other side, performance in megaproject management is strikingly poor and has not improved for the 70-year period for which comparable data are available, at least not when measured in terms of cost overruns, schedule delays, and benefit shortfalls.

For six days in March of 2021, the world watched with a mixture of frustration and glee as global shipping and logistics ground to halt when a very large boat got very stuck inside the Suez Canal. Some offered sardonic solutions, including:, “My ambitious plan to free the boat is to push a huge cotton swab up the canal” (@karlesharks). Others welcome the simplicity of the event, noting, “The boat? It's just stuck. Stuff won't go. Boat needs to be not stuck. That's it” (@hpheisler). The legibility of the problem (a very big and very stuck boat in a narrow canal), and the magnitude of its effect, was undergirded by a complex system of global shipping trade. The Suez is one canal amongst hundreds that carry an estimated 70% of all global freight. In 2015, this accounted for 75.6 trillion tonne-kilometers (a freight measure for moving 1000kg one kilometer).

The Suez Canal, along with several other major canals and shipping lanes, is a global chokepoint, a critical node in the global shipping system that, when incapacitated, can upend commerce at a planetary scale. Chokepoints like this are emblematic of the kind of robust-yet-fragile systems that global capitalism produces. Nearly 12% of global shipping trade passes through the Suez canal annually, accounting for over a trillion dollars worth of goods.

Mega projects, by their very definition of any project over 1 billion USD, are reflective of enormous capital investment. These are not limited to projects of the built environment, but include military technologies and weapons, R&D for medicine development, and spacecraft. Mapped here, against global population density, are physical projects including, disaster cleanup, energy infrastructure, sports complexes, transportation development, urban renewals, and investments in hydrological management. Unsurprisingly, many projects that rise to the level of a megaproject are scattered throughout the global north, with the US accounting for a large proportion of them. The number of megaprojects is set to rise, especially amongst the complexity and increasing scale of proposed solutions to the Climate Crisis.

The projects are categorized as disaster cleanups (salmon), energy projects (red), science projects (purple), sports projects (green), transportation projects (white-outlined circles), urban renewals (yellow),and water related projects (blue) are represented by different circles. overlaid on a base map of population density.

Despite its enormous impact on global shipping, The Suez Canal is not considered a megaproject. A megaproject is commonly understood as any project that has nominally spent at least one billion USD on its research, development, and implementation.

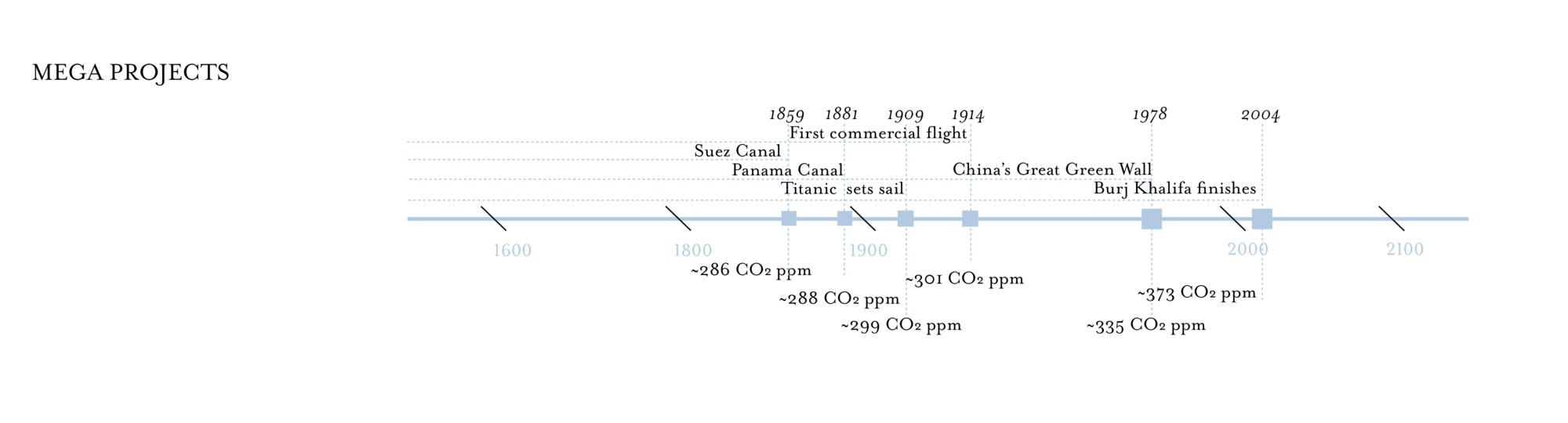

But focusing solely on the nominal cost of a project severely limits the historical scope of megaprojects, rendering them a product of the 20th and 21st century even as we approach the era of teraprojects (1 trillion dollar projects). Megaproject scholar, Brent Flyvbjerg, challenges this approach, noting how projects of this magnitude “are designed to ambitiously change the structure of society, as opposed to smaller and more conventional projects that are ‘trait taking’, that is, they fit into pre-existing structures and do not attempt to modify these.”

Megaprojects, under Flyvbjerg’s definition, operate at local, regional, and global scales, seeking to fundamentally alter markets, political formations, and everything else that implies. This framing allows for historical inquiries into projects that do not meet the nominal threshold of one billion dollars to be considered: the Suez canal, adjusted for inflation would have cost over two billion dollars today. It also opens the category up to colonial projects in Africa, whose explicit goals were to reshape the African continent, both physically and socially, for the benefit of the European elite. It helpfully reorients one’s analysis away from project costs and toward project impacts.

If people knew the real cost from the start, nothing would ever be approved. The idea is to get going. Start digging a hole and make it so big, there’s no alternative to coming up with the money to fill it in.

Flyvbjerg’s more lenient framing of megaprojects rooted in societal impact rather than strict monetary value illuminates the role designers have played in reimagining and restructuring social and spatial relations through the built environment. Given the scale, complexity, and funding requirements, traditionally defined megaprojects are often the purview of civil and structural engineers. The Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building and the only megaproject delivered through a single building, is a notable exception to the list.

Architectural theorist Reyner Banham, in his 1976 book, Megastructure, alludes to the ongoing jump in scale from that of a designed city, to a designed continent, and finally to a designed planet. He describes North America as “the part of the world that had problems vast enough to require ‘visionary’ solutions and the biggest technological resources for dealing with them, and that sheer dimensional bigness was an essential part of the solution to these continent-sized problems.”

Architectural critic Kate Wagner notes the similarity between the plague of issues today and the 1960s when these imaginaries were last palatable, concluding, “It’s no surprise that half-baked ideas from this former period have re-emerged in their current, even less inspiring forms.”

The scale, complexity, and breadth of stakeholders in megaprojects makes them notoriously difficult to manage from conceptual design, funding, construction, and demonstration of success. Flyvjberg identifies the “Iron Law of Megaprojects” as over budget, over time, over and over again. Backing this law is a dizzying statistic: 1 in 1000 megaprojects are finished on time, on budget, and with the promised benefits. Despite this difficulty, these projects are often high-profile and promise significant change for enormous numbers of people, making them the ideal bait for political self-congratulation even before the project is finished. Project costs are purposely underestimated to ensure buy-in from public constituents, especially in places like California where voters must approve all new taxation measures. Flyvjberg spears this practice by pointing to the importance placed on the sales pitch, how they look on paper, over the real-world achievable benefit, going on to say, “the projects that look best on paperare the projects with the largest cost underestimates and benefit overstatements.”

Understanding the limitations of megaprojects to be implemented are crucial to effectively utilizing the massive amounts of money that are dumped into infrastructural projects across the globe. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates global infrastructure spending per year to be 3.4 trillion or 4% of total global GDP. That number is likely to rise in the face of the Climate Crisis and the ongoing fetishization of geoengineering, carbon capture and sequestration, and other technological fixes.

Infrastructure spending is inherently a catalyst. It tends to spur additional investment, a phenomenon Mariana Mazuccato refers to as “crowding in” investment—the idea that public investment in any sector will inherently crowd in private sector investments.

Unfortunately, focusing on the logistics of a project often cuts out what happens beyond the site of construction, resource supply chains, and the routes between sites of extraction, manufacturing, and construction. People and places are reduced to their capacities with little concern for the impacts these projects will have on the material well-being. Introducing these concerns back into infrastructural projects will necessitate refusing to abstract landscape systems and peoples into the calculable language of logistics and instead focus on the material impacts of megaprojects in local economies, ecosystems, and lives as a determining factor in their success. For Davis, Holmes, and Milligan, landscape based approaches, which is to say focusing on the material realities of landscapes, “foregrounds the fact that certain values or uses are chosen over others, one way of life over many other possibilities.”