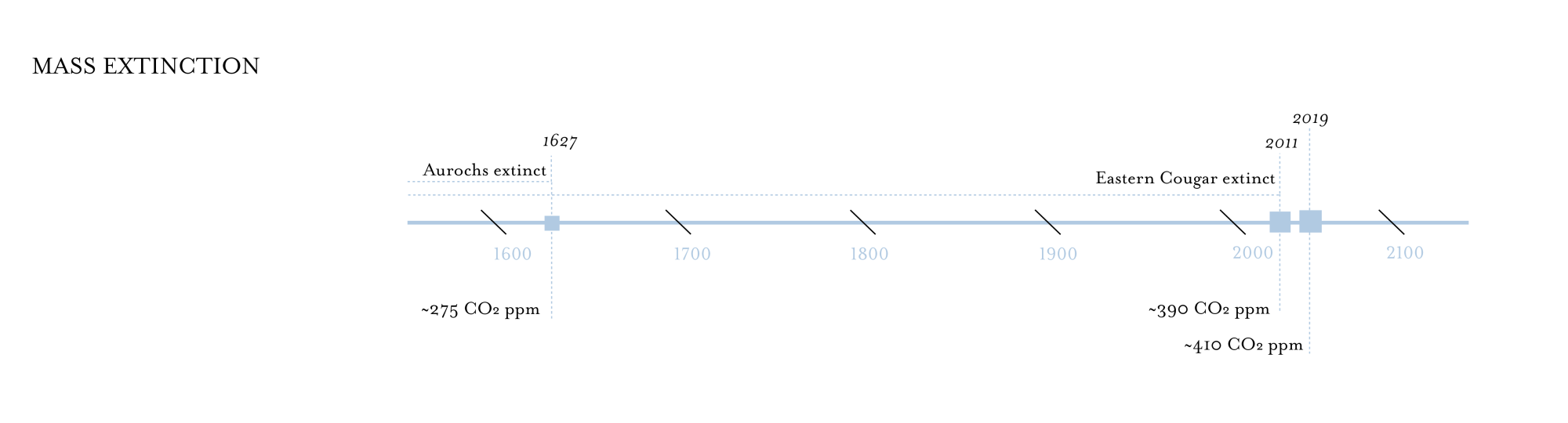

Mass extinction has often been viewed as an historical event—a phenomenon to be measured and defined in retrospect. Five previous events marked in the fossil record are theorized as the result of sudden shifts in climatic conditions, volcanic eruptions, and asteroid impacts blotting out the sun. The Ordovician Mass Extinction, the first known mass extinction at 440 million years ago, occurred in two distinct phases: the first, a global ice age that disastrously lowered temperatures and sea levels; the second, the rapid melting of accumulated ice disturbed the oxygen carrying capacity of the ocean, causing a second rapid climatic shift that species were unable to effectively adapt to. The Permian Mass Extinction, 250 million years ago, is the largest recorded extinction event, with an estimated 96% of life going extinct. Scientists are still undecided about the causal agent of the extinction, but popular theories involve a chain of events including extreme volcanic eruptions and asteroid impacts that increased the methane content in the atmosphere, effectively choking species due to decreased oxygen levels. The extinction event famous for ending the reign of the dinosaurs, the K-Pg Extinction (formerly K-T Extinction), was the result of a massive asteroid impacting the earth, blowing particulates into the air which produced a global winter and spurred climatic change across the globe. But the urbanization of the planet and the cascading, geochemical chaos of climate change have, for perhaps the first time, shown humans to be a causal agent in a new, sixth mass extinction. The previous extinctions have been catalyzed by different geological and interplanetary events, but the resultant rapid changes in the global climate have been the real species killer. Since the 1980s scientists have been discussing something different: an ongoing projective mass extinction event. Assuming the lack of a planetary consciousness of species living through previous mass extinction events, this may be the first time a species has had a planetary awareness that life, and the worlds it constitutes, is irreparably and actively being lost.

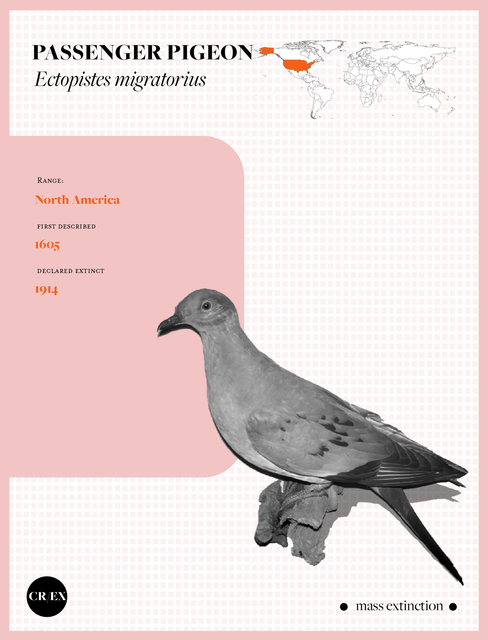

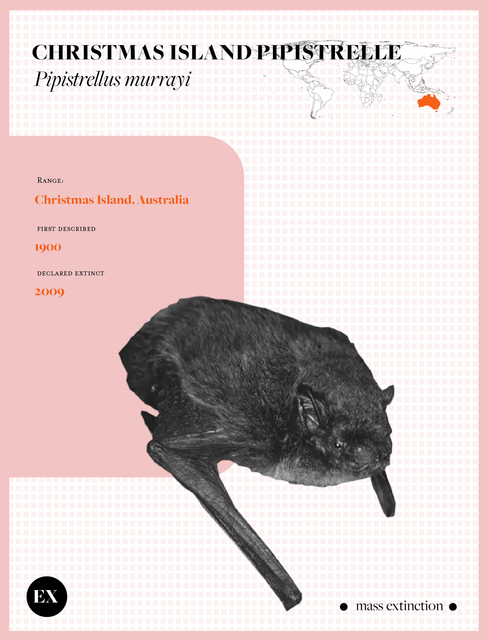

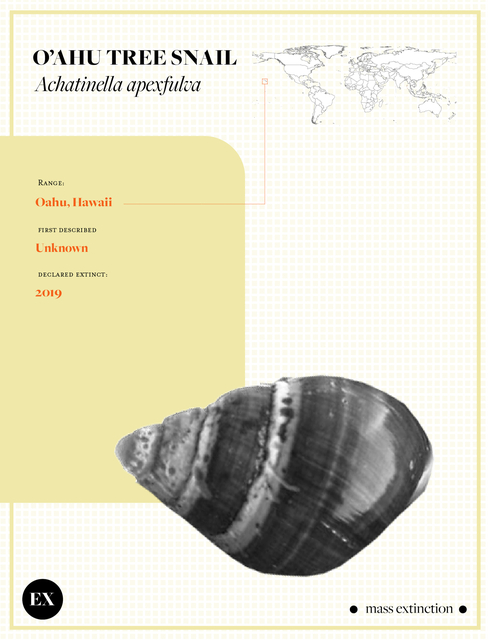

To date, 799 species of the 1.9 million known species have been officially designated as extinct. Given that less than 10% of species on this planet are known to science, this figure is, in all likelihood, a dramatic undercounting of species extinction. The dodo, hunted into extinction by humans in 1681, stands as the cultural symbol of extinction, marking the decline in biodiversity as the direct result of humans. Losing nearly 800 species alone should be enough to spark a frightening revelation on humanity’s impact on the potential worlds of species lost. Unfortunately, reader, it has not. Some scientists note that many extinction estimates ignore invertebrates, the most numerous category of species on the planet, in favor of charismatic terrestrial fauna. By factoring in loss of invertebrate species Regnier et al. (2015) estimates the true reflection of current species loss is around 7% (a huge jump from the .04% of definitively recorded extinct species). For them, the loss of a species is a projective activity, as the lack of observation is no longer the principle barrier to measuring and classifying a species’ extinction. Through their study, Regnier and her team have developed an approach that “accepts some level of uncertainty for individual species, but at a large scale, it aims to provide an estimate of the true level of extinction...” (Regnier, et. al). A key component of Regnier’s methodology relies on assessing the conditions that might lead to a species being extinct and the subsequent probability of those conditions being met. Eucalodium moussonianum, a species of snail not seen since its original observation in Vera Cruz, Mexico in 1872, has no known habitat, making it “nearly impossible” to conduct an extinction establishment-survey. On the other hand, Amastra baldwiniana, a snail native to the island of Maui, can be declared extinct, despite no official survey, because of the relative size of its territory, the introduction of invasive species, and the changes in land-use resulting in habitat loss.

Model-based extinction calculations can account for nuances that observation-based definitions often overlook. Newbold, in another model-based extinction study, examines changes in land-use as reflective of environments that are ‘biotically comprised’ to understand if terrestrial biodiversity has passed the threshold for biodiversity loss. Understanding the planetary boundary (or the point of no return for biodiversity) for intact species has been crossed, which Newbold identifies as 90% species intactness, is one way of marking an extinction event, even in its earliest millennia—a kind of extinction spiral that may mean a species can still be observed but that it cannot, in all likelihood, survive given its limited population size and gene pool. Newbold and his team found that the average level of species intactness was 84.6% across the globe. In other words, the planet is experiencing another mass extinction.

The kinds of quantitative, simulation-driven explorations of extinction bring together species we know intimately, species we know little about, and species that scientists have not yet observed. They often rely heavily on ecological systems theory, capturing the interdependence of species to one another—and, through measures of presence and absence of particular species, they often estimate the broader biodiversity loss that comes from extinction or extirpation. Put another way, they treat the individual species and components that comprise ecosystem measures "like Muir Webs" as highly correlated—when observed species in the web dwindle, scientists can often assume that the same is true across much of the other species in that system. Anthropologist Zoe Todd speaks directly to the interscalar relationship between local loss and the global climate crisis when she says: “While we may experience the loss of fish in Alberta as a local loss, it is arguably linked to the broader catastrophic losses across geographies, territories, moments.” This cultural focus reattunes the question of extinction to both the cultural and scientific, the global and local.

The co-constituted relationships between local species and Indigenous peoples is especially at risk as the various forces perpetuating the Climate Crisis converge to threaten Indigenous kinships and ways of being. For the Inuvialuit people who live in Paulatuuq, Alberta, fish are a source of food and non-human persons. Their presence in local lakes and rivers constitutes a kinship, one with a complicated history of spurring on and subverting settler colonial projects. By connecting this particular non-human relationship to the global legacy of colonization, Todd connects the potential loss of a species to ongoing practices of dispossession for Indigenous peoples, going on to say, “we need to consider that a land without fish is one that will not only leave us physically bereft, but also intellectually and spiritually bereft as well.” While debates on observation or model-based extinction calculations focus on how to calculate the rate of species extinction, they do little to attenuate the sense of loss accompanying mass extinction discourse. Ursula K. Heise in her book, Imagining Extinction, has begun to explore the cultural value of extinction: how it is leveraged in conservation discourse, across different media (especially literature), and as a reflection of a particular moral standing. For Heise, inquiries into representations of specific species extinctions (or the threat thereof) become stand-ins for larger critiques or support of the forces which threaten or eradicate them. For example, the processes of Modernity have produced two different affective responses towards species extinctions: lamenting the potential loss of giant pandas and the celebration of polio’s eradication. By examining how different extinction events are written about, visualized, and discussed, the implicit value of the worlds and systems that sustain species is revealed, thus concerns about habitat loss from increased agricultural land-use which threaten the giant pandas can be housed under the same banner of extinction that lauds the scientific achievement of eradicating a deadly disease. In order to conceptually grapple with the time scale and speed of future extinctions, Heise adopts the language of imagination, in essence a practice of thinking through which interspecies relationships comprise the world of the future and elaborating on the systems and ideologies that must be developed to achieve that world through works of fiction, illustration, film, and other media. Interrogating, and to some extent preparing for, the inevitable loss of life that will occur throughout the next century and beyond is a crucial component of developing meaningful activism and advocacy against the worst version of the Sixth Mass Extinction. Living with extinction will increasingly become a necessary component of life in the 21st century if the planet is unable to dismantle the global web of petro-capitalism that is snuffing out species and human and non-human ways of life. For millions of species, there is no life after the Climate Crisis.