The agents of planning are usually boring; the planning process is boring; the implementation of plans is always boring. In a democracy boredom works for bureaucracies and corporations as smell works for skunk. It keeps danger away. Power does not have to be exercised behind the scenes. It can be open. The audience is asleep. The modern world is forged amidst our inattention.

For Japanese hydrologists and engineers in the 1950s and 1960s, Tennessee was a familiar word. During the U.S. occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952, American experiments with democratic control of infrastructure and utilities forged throughout the New Deal began to transmit across the Pacific and into war torn Japan.

The trans-Pacific transmission of engineering expertise was hastened by the 1949 translation of David E. Lilienthan’s TVA: Democracy on the March, the first insider account of the utility’s development over the course of the New Deal era. It helped capture the imaginations of engineers and political leaders tasked with leading postwar Japan into a new, modern era–one that would increasingly become organized around hydroelectric power and similar kinds of industrial-scale energy production.

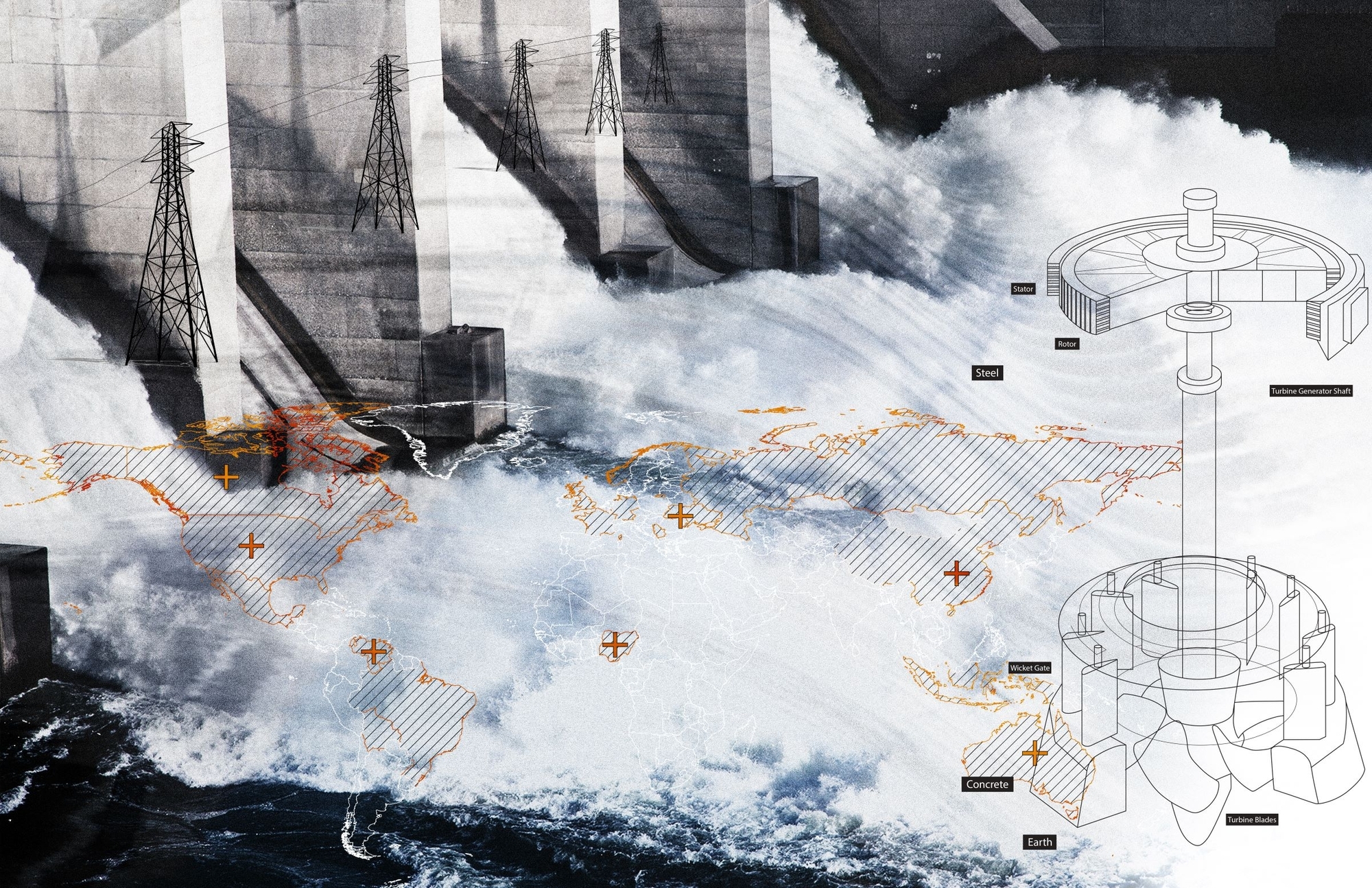

Major hydroelectric projects are dependent on control. Dams require management of entire hydrological systems to ensure a consistent flow of water over the power-producing turbines. These projects have altered riverine ecology across vast territories, displaced Indigenous populations, and converted rural environments into power-producing regions for their urban counterparts.

Japan was not alone in utilizing the TVA model. Lilenthal, director of the TVA project, framed the utility’s ideals and operations as infrastructural models of democracy, positioning it inapposite to Soviet models of modernization well into the Cold War.

The TVA model became a key American export as the nation sought to spread its cultural and economic might under the banner of “spreading democracy”. Odette Keun writes in her 1935 A Foreigner Looks at the TVA, “the immortal contribution of the TVA to Liberalism, not only in America, but all over the world, is the blueprint it has drawn....”

On both sides of the Pacific, hydroelectric power became a tool for converting rural water systems into reliable, baseload power for rapidly urbanizing centers.

White begins the conclusion to his book stating: “The Columbia had become an organic machine which human beings manage without fully understanding what they have created.”

Hydroelectric power, itself, is not antithetical to the goals of the Green New Deal, but by leashing it to the runaway horse of neoliberal economics, its ability to intertwine local economies, peoples, and ecologies has been severely limited. The Tennessee Valley Authority worked for local people, providing them a semblance of control in the regional planning efforts of their geographies.