Collectively speaking, our online activities represent a significant portion of the world’s industrial output. If the Cloud were a country it would be the sixth largest consumer of electricity on the planet.

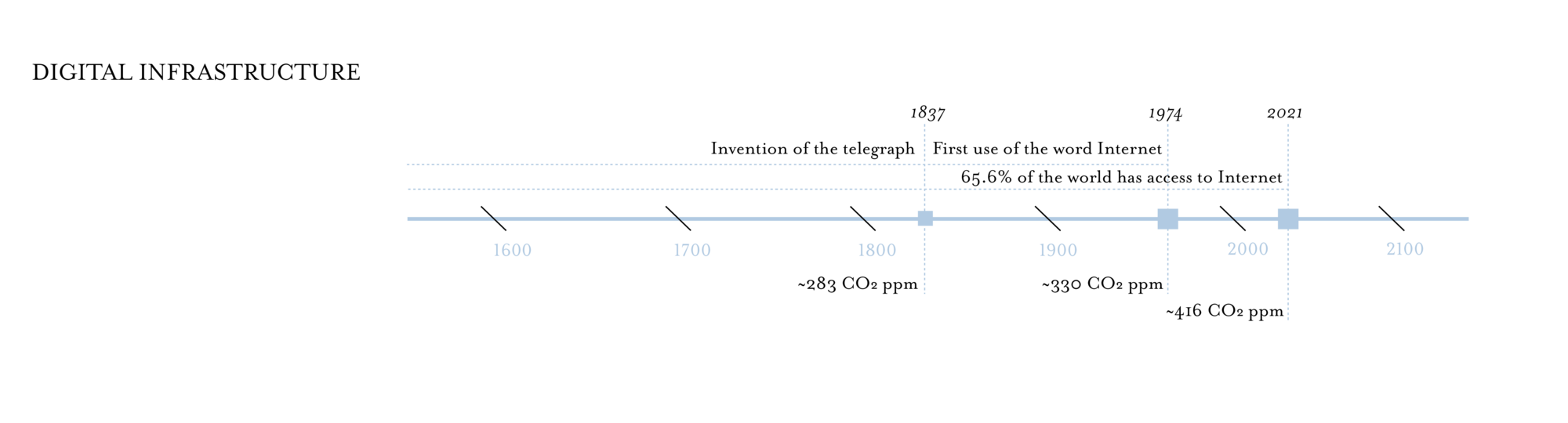

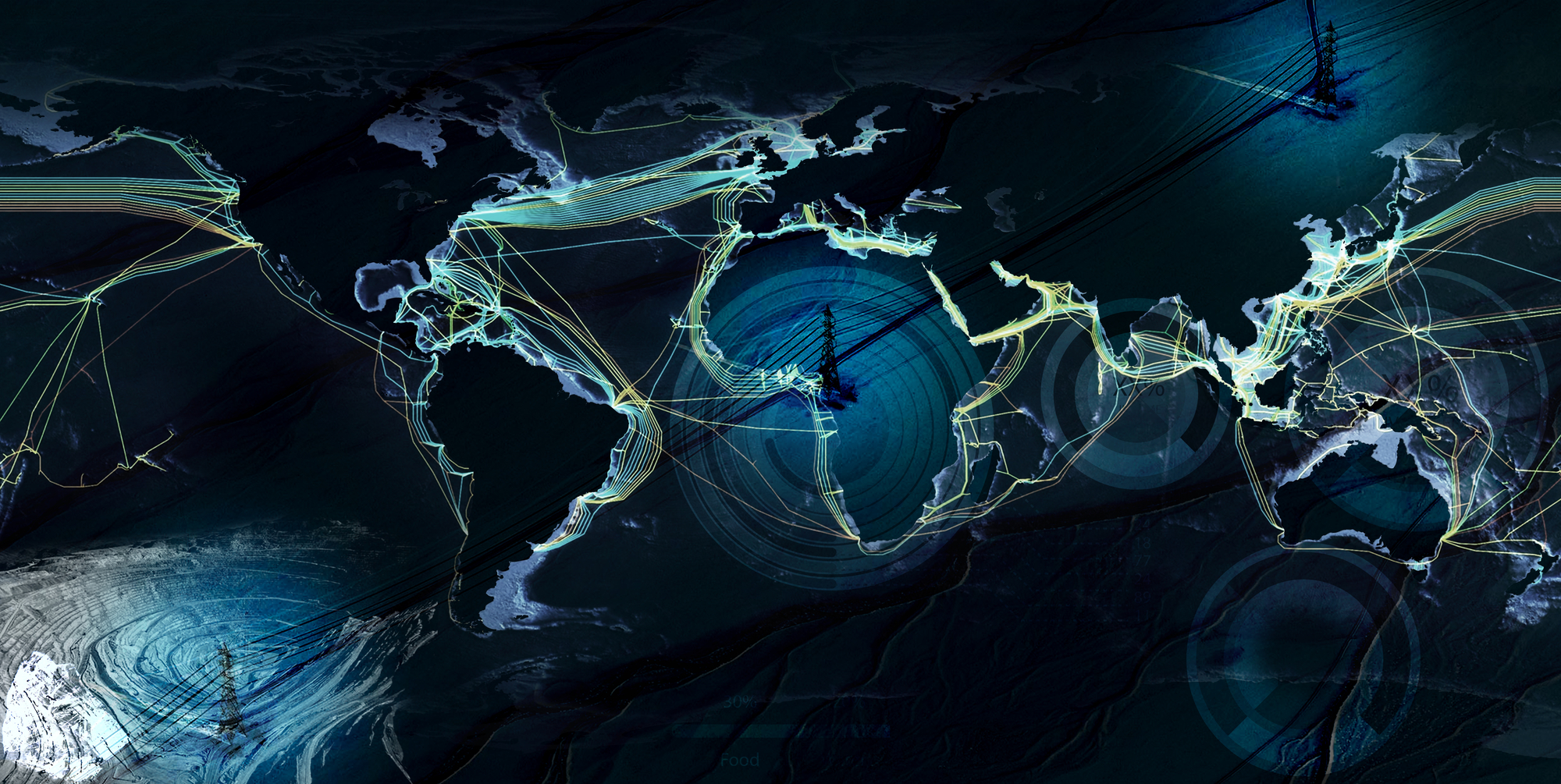

The Internet is more than its physical self. It is also everything it touches, and everything it rests upon. While it may have begun in earnest as a couple of mammoth mainframes and a handful of wayward cables draped across an arid stretch of the California coast, what has come to be known as The Internet has burrowed itself into rock, bodies, and atmospheres in manners and scales we do not yet fully comprehend. It seems omniscient and omnipresent, an inescapable feature of contemporary life. The decarbonization of the Internet requires better understanding of its physical composition. The material footprint of the Internet extends far wider than just cables, data centers, and cell phones. The Internet is also the energy grids that support it, the global shipping and logistics spaces through which digital devices are manufactured, and, perhaps most importantly, the vast expanses of raw resource extraction that feed it, as digital living would be rendered impossible without ubiquitous access to critical metals like cobalt, tantalum, and rare earth minerals.

The Internet is not an easily mappable thing. It alludes simple geographic placement, comprising physical and social infrastructure that have extensively altered the daily lives of billions of peoples. As the internet expands into more material and spatial territories, the ineffability of this expanse will become ever more pronounced. This transition has been unprecedently swift, offering a clear example of the scale of physical and social infrastructural overhaul that can be achieved globally. Climate infrastructure and systems of climate justice need to operate at the speed and scale of the internet’s deployment to effectively address the Climate Crisis in the first half of the 21st century.

In the last few years, we have heard Google

Tech companies attempt to control the rhetoric of decarbonization and sustainability in two big ways. First, these corporate sustainability initiatives reflect a reliance on our understanding of a carbon neutral Internet as an outcome dependent on big tech companies, and their willingness to sacrifice shareholder earnings on the path to rapid decarbonization. This is a strategic framing, rooted firmly in neoliberal politics, meant to inure trust in our tech titans as the proper stewards of climate futures and to continue diminishing the role of the public sector in regulating and investing in such climate and infrastructural matters. A just decarbonization entails a reconsideration of what the Internet is (materially speaking), how it is held together, where its waste comes from, and where that waste goes. It may also require a reframing of the Internet as a public good, operated like a public utility, with democratic ownership driving its decarbonized future.

Second, for decades, tech companies have incubated strategies to frame e-waste as solely a post-consumer problem, for which responsibility principally lies with consumers to properly discard devices. While tremendous amounts of waste and carbon are produced and released at all points in the tech supply chain, not just on the post-consumer side, none of these waste streams have ever been officially treated as e-waste, but rather as problems for someone else, some other industry, discrete from what the Internet claims to be.

Understanding e-waste as only or even primarily a problem of too many objects obscures the vast amounts of waste and carbon emissions generated during mining and manufacturing processes that elude most accounting measures. While companies like Apple and Google like to cite vast improvements in energy efficiency and carbon neutrality in the operation of their devices and data centers

The only path to a just, carbon-neutral digital life is through the cultivation of a coordinated, inter-scalar understanding of what, where, and how the Internet is actually comprised and maintained. This means, in part, broadening our concept of the Internet beyond just its connective tissue–all the cables, devices, data centers, and the like. We must develop better methods of understanding how infrastructures of data, energy production, resource extraction, logistics, and labor are entangled nonlinearly across multiple scales–and then we need to build solidarity through these scales. From the mining of crucial minerals like cobalt, tin, and rare earths, to silicon foundries and widespread manufacturing infrastructures, to the massive energy regimes supporting the global data center industry, all the way to the unevenly regulated post-consumer e-waste disposal, reclamation, and recycling industry–all of these processes are deeply bound up with one another.

The Internet is a “transnational infrastructure”

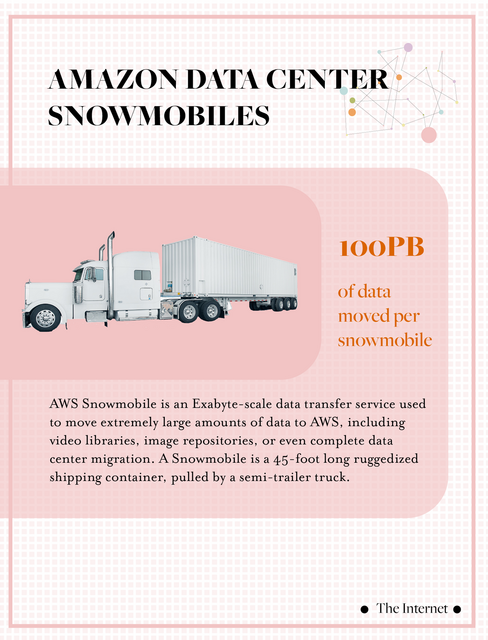

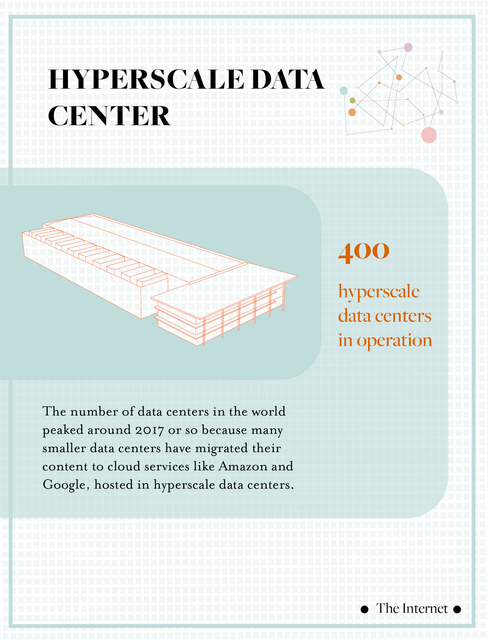

As an example, maps of the global data center industry are becoming increasingly common, and the data center has become a popular site of analysis for scholars and journalists grappling with the material footprint of the Internet. However, data centers are not static objects. They are persistently maintained, upgraded, and downgraded, as server racks, hard disk drives, cooling units, and all sorts of other mechanical paraphernalia flow endlessly in and out of their doors. In the case of hard drives, about every two or three years, any given data center’s storage infrastructure is completely new. The metals for hard drives (including rare earth metals, see map) are mined, smelted, and machined into storage units that live short, high-intensity lives, and then become discards, living second and third lives as recycled scrap metal, leaving all sorts of peripheral, toxic traces in their wake. Nanna Bonde Thylstrup refers to this phenomenon as “data out of place”

The discardscapes of clicking are generated in all Earth environments—atmospheric, marine, and terrestrial.

An international Green New Deal for the Internet requires a foundational reassessment of what it means to move information through the world, and that begins with breaking with linear metaphors, and embracing the dynamic, volumetric “interplay”