What we are doing to the forests of the world is but a mirror reflection of what we are doing to ourselves and to one another.

In September of 2014, the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF) endorsed the UN Climate Summit.

Since its introduction, the NYDF has amassed more than 200 signatories, comprising national and sub-national governments, multinational corporations, indigenous rights groups, and NGOs from around the globe. Together these entities are hoping to be able to leverage their collective might and redefine the currently extractive relationship to the world’s forests. The NYDF calls for signatories to adapt new policies, alter supply chains, and reconfigure land uses in an attempt to end natural forest loss by 2030. As an interim benchmark, natural forest loss was to be halved from 2014 values (13 million hectares of annual forest loss) by 2020. To be on track with the goals of annual forest loss would have to fall to 6.5 million hectares per year. This number alone is an astounding amount of forest lost annually, but reducing forest loss by half would have been remarkable progress. By all accounts this goal has not been achieved: annual forest loss has increased 43% over the 2000-2018 period. To the NYDF’s credit (or perhaps delusion) they have continued with their initial goal of zero natural forest loss by 2030, meaning annual forest loss will have to be reduced by over 2 million hectares a year. The resolution faces one major challenge in reaching its goal, it is non-binding, meaning there are no enforcement methods or disincentives for signatories who have not aided in reducing natural forest loss.

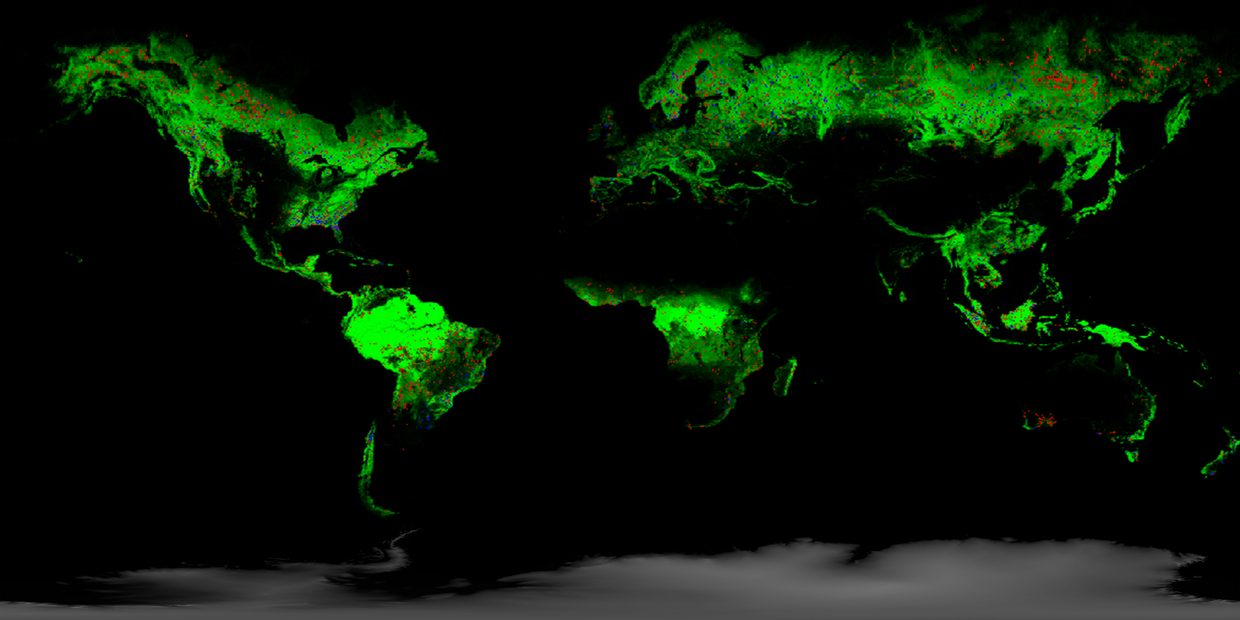

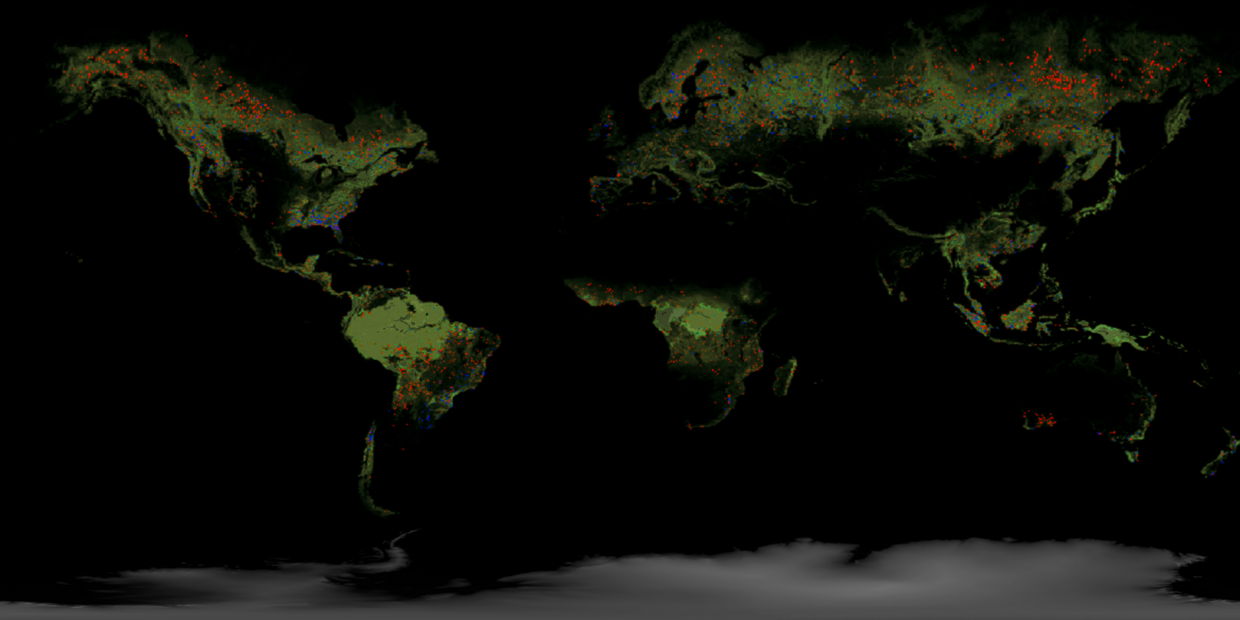

Large swaths of the world today are forested, shown above in bright green. Increasing urban sprawl, forest fragmentation, and unsustainable agricultural practices pose serious risks to the continued existence of robust forest ecosystems. Between 1990 and 2020 there were more instances of forest loss (red dots) than forest growth (blue dots), a pattern that is expected to continue and worsen throughout the 21st century. 1

- 1Data for tree cover and change can be found at: Hansen, M. C., et al. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342, no. 6160 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693. Visualized on Google Earth Engine. https://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest

Friedl, M., D. Sulla-Menashe. MCD12Q1 MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V006. 2019, distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd12q1v006/

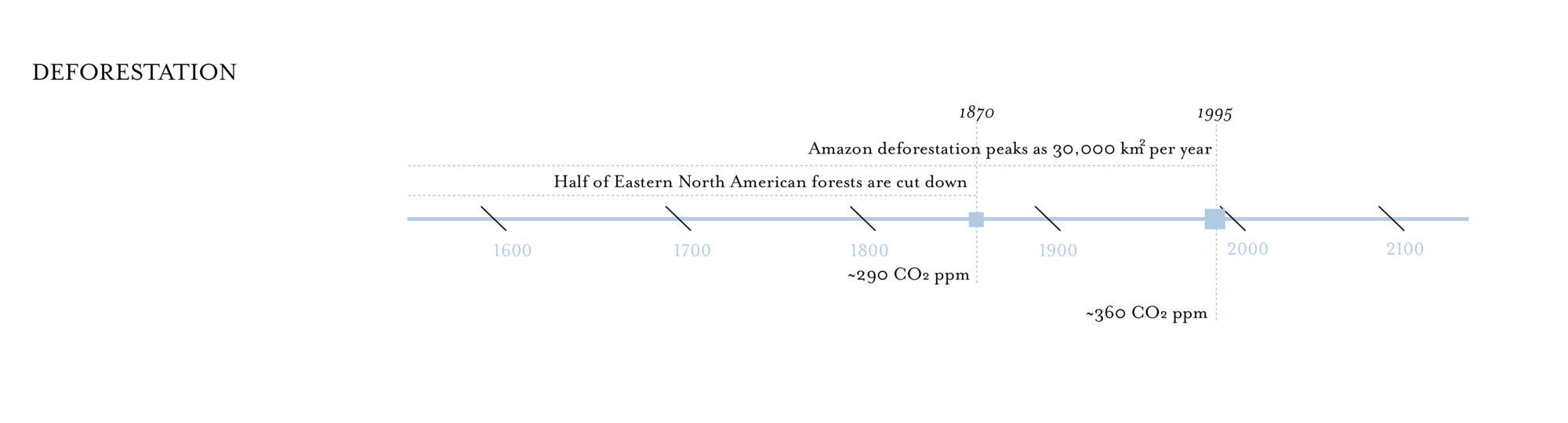

The extent of forests around the world has declined by an estimated 16.4 million km2 (36% of the historical extent) over the last 200 years.

What once-forested land transitions to is also an important factor in determining the extent to which warming will increase as a result of deforestation. This is because forests have a low albedo, a measure of how much sunlight is reflected back off the earth into the atmosphere. Permanent changes in land use from forested land towards bare earth or concrete increase the albedo, increasing the warming potential in addition to releasing the carbon stored in the felled trees.

Measuring, managing, and mitigating global forest loss is crucial to ensuring the planet remains habitable throughout the 21st century. Deforestation of large areas of tropical forests have been found to spark global changes in rainfall patterns in certain regions of the world, leading to stress on agricultural systems within far off regions from the original site of deforestation.

You know, a tree is a tree, how many more do you need to look at.

Afforestation projects have received considerable philanthropic and media attention, making them popular commitments for NGOs and governments the world over in slowing the Climate Crisis—a product of the political salience of trees (who could oppose them?), the ease of committing to such a planting program without ever worrying about oversight or accountability, and the reality that tree planting neither sequesters carbon on a geologic timescale nor requires any real confrontation with the primary agent of global climate change, the fossil fuel industry. High profile programs like Pakistan’s 10 Billion Tree Tsunami and Subsaharan Africa’s Great Green Wall have garnered much praise for their sustainable-minded commitments, but the two projects have resulted in varying levels of success.

Pakistan’s tree planting efforts began at a billion trees in 2015 by the sub-national government of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region. The project’s success upon completion in 2017, sparked a countrywide initiative: 10 billion trees by 2023. The project to date faces its share of supporters and critics. The government has claimed the program has created 85,000 jobs, however concerns over effective forestry planning and the impact of massive tree growth on already strained water supplies have led some environmentalists to raise concern over the project’s overall long-term benefit for the country. Other environmentalists are holding out on the belief that the increased forest cover will alter local rainfall patterns and alleviate the water shortages experienced today.

The Great Green Wall in Africa began as a strictly tree planting program in the effort to stave off creeping desertification of the Sahara. This was not an effective strategy for the local context, as Chris Reij from the World Resources Institute puts it, “if all the trees that had been planted in the Sahara since the early 1980s had survived, it would look like Amazonia.”

Increasing focus on the health of our existing forests and in tree planting efforts are often seen as signs of changing tides in the fight against the Climate Crisis. This attention, while certainly advantageous, can become a distraction from the necessary work of decarbonizing the economy. A singular focus on afforestation allows fossil-fuel companies like Shell to claim planting 700 million trees in the Amazon will keep warming under 1.5C and to say nothing of their historical and continued role in deepening the groves of inequality that coincide with the effects of the Climate Crisis.